You don’t need to look too far to see the negative impact that labor shortages are having on the economy. Long lines at grocery stores, restaurants with reduced hours, and childcare facilities capping enrollment are just some of the examples. As a long-time market observer, I find these persistent shortages somewhat perplexing. Under standard economic theory, when the supply of something falls short, price (in this case wage) increases pull sufficient additional supply into the market until supply and demand fall into balance

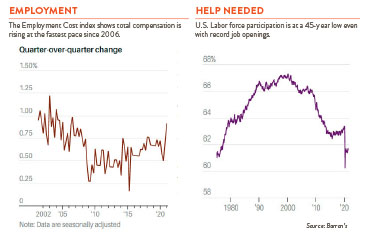

While there are a lot of reasons that labor markets don’t function exactly like the market for say, watermelons, as a general rule this dynamic should hold true. But take a look at the two charts below; the one on the left tracks the Employment Cost Index and the one on the right shows the Labor Force Participation Rate. The takeaway? Record increases in compensation are failing to draw people into the workforce. This is particularly true at the low end of the wage scale. In a recent study, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that for those earning less than $60,000 and without a college degree, the “reservation” wage (the lowest wage that an unemployed worker will accept at a new position) rose 26% between March 2020 and March 2021. For those making more than $60,000 and with college degrees, the reservation wage rose only between 3% and 6%.

Many labor economists believe this is just a short-term problem resulting from the confluence of two opposing forces: the unprecedented demand for workers resulting from economic reopening and the COVID-induced disruption in the supply of labor. Once the pandemic recedes, schools and childcare facilities fully reopen, and enhanced employment benefits expire, workers will return to the workplace and all will be well.

But I think some of what we are seeing is the result of structural changes in the nation’s labor markets that have been brewing for years. Like much of the developed world, the pool of available labor in the U.S. is shrinking. The oldest baby boomers turn 75 this year. This large cohort has stayed on the job longer than any earlier generation but is now starting to call it quits. Unfortunately, declining birth rates and lower levels of immigration are failing to offset these retirements. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the U.S. workforce is expected to grow at an anemic 0.3%-0.4% annual rate for the rest of this decade, less than half the 0.8% rate witnessed between 2000-2020.

A skills mismatch also appears to be impacting employment trends. Consider that the just released July employment report showed 10.1 million job openings — a level that exceeds the estimated 8.7 million unemployed people today. These numbers suggest that our economic problem today is less about creating jobs and more about getting the right people into the right jobs. Finally, while the pandemic has created unprecedented care issues for millions of families, this is not a new issue. In a recent Barron’s op-ed piece, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo pointed out that even before the pandemic a full 43% of parents reported struggling to an find adequate childcare facility. An aging demographic suggests that care burdens at both ends of the age spectrum will only increase in the years ahead.

The good news is that much can be done about many of these structural labor market challenges. Accommodations to allow older workers to stay on the job longer will help, as will policies to support employees with care needs. Training and education aimed at narrowing the skills gap too will be critical. These remedies have been discussed for years. Labor market conditions today may now make them essential.