The creation and commercialization of plastic may be one of the crowning achievements of the twentieth century. It may also end up being one of the most harmful to humanity and the earth.

For better, and certainly for worse, disposable plastic products are perhaps synonymous with a stereotype of America, like fast food and baseball. The story, as told by Alexander Clapp in his new book, Waste Wars, begins during World War II when the wartime economy sought a cheap, synthetic material. Plastic, the byproduct of fossil fuel production, was the answer, and it soon rolled off assembly lines and into our daily lives.

Crucially, one of the results was the advent of single-use products. The idea was simple: the product was cheap, and you were supposed to feel OK about using it once or twice and throwing it away. This phenomenon opened new doors for companies but also led to a massive increase in waste. Since then, billions upon billions of pounds of plastic have been produced – and will persist for thousands of years.

This trend did not go unnoticed. One early solution to the mounting piles of plastic waste was to burn them. Another solution was to recycle them. The marketing was smoother for the latter, and recycling became the feel-good solution for the masses. Use your plastic once and it will be used again in another life.

The reality is not so clean. First, there are many varieties of plastic and not all of them can be blended together. Additionally, the pieces that can be recycled can only be used once or twice more before permanent disposal is required—eventually it becomes trash. Another conundrum is that producing plastic is cheap while recycling it is not. Without economic incentive, even what is recyclable becomes less than desirable for industry. And, of course, the process can be toxic. There are many chemical additives to plastic which are released during the recycling process.

So what was to be done? Globalization offered one solution. Enterprising individuals—trash brokers—from lower income countries saw an opportunity to buy plastic waste from the U.S. for use in cheaply produced products back home. Recycling efforts were redoubled, and the developed world now had a garbage chute for its plastic. But this process has come at a cost. Those lower income countries who agreed to take the plastic were also among those with the least stringent environmental regulations. The imported plastics were used until they could not be, then often dumped and burned in the countryside.

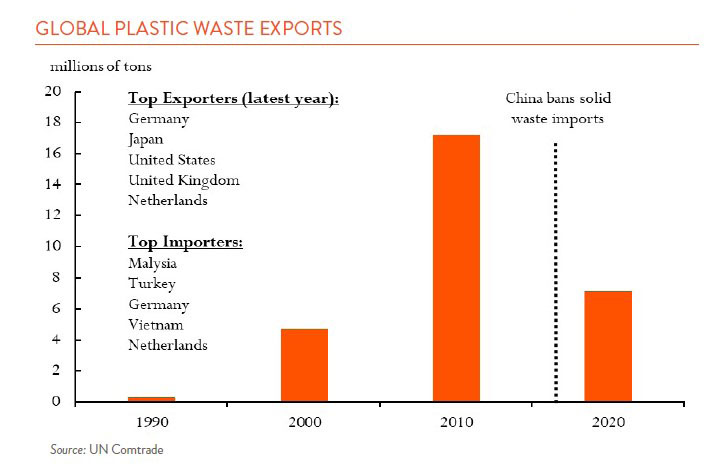

This cycle has continued over time. The destination countries have changed, notably in 2018 when China banned imports of plastic waste, but the plastic trade remains the same. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, only 9% of plastic gets recycled in the U.S. The amount that is exported is hard to come by, but estimates range from 2%-5% of all U.S. plastic waste, or around one million tons of the stuff (see chart below for global export figures).

I wish our story ended here, sour note that it is, but it gets grimmer. Microscopic pieces of plastic, now referred to as micro- or nano-plastics, have been found all over the world, including inside humans. Studies linking microplastics to health issues such as heart disease, stroke, cancers, hormone imbalances, and birth defects have been popping up left and right. Microplastics float in the air and are inhaled, they enter our skin when we handle plastic materials or wear it next to our skin (polyester and nylon are derived from plastic), and enter our food through packaging.

Plastic has done wonders for the world. Technological innovation, medical intervention, improvement in food storage – the list goes on. However, we are seeing the consequences. How serious they end up being, we do not yet know. In the meantime, I continue to use many plastic items in my life, but for my children, it is metal water bottles and glass containers.