The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences recently awarded the Nobel Prize to three economists for explaining how technological advances drive lasting economic growth. Joel Mokyr won for identifying “the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress,” while Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt won jointly “for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction.” It may seem obvious today that innovation drives prosperity, but a key insight of these laureates was that historically, sustained growth has been the exception, not the rule.

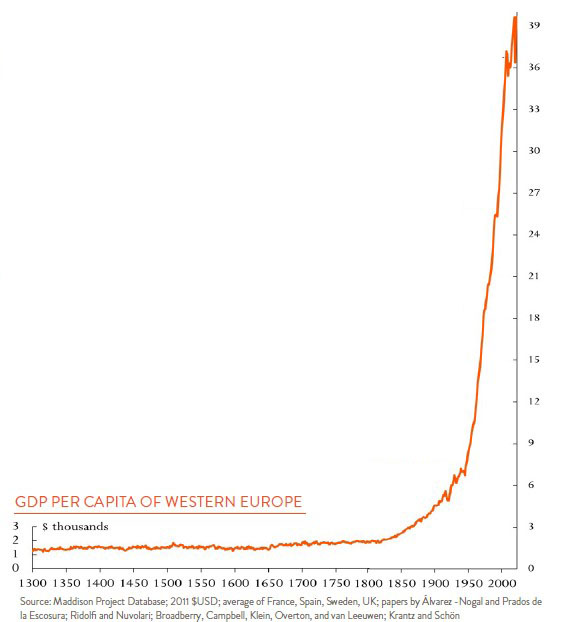

We like to zoom out to the big picture, and today we will take the very long view indeed. The chart at the right shows estimates of GDP per capita for western Europe going back to the year 1300. Notice two things: first, growth mostly stagnated for 500 years despite plenty of major innovations—the Prize literature cites the proliferation of windmills and the heavy plough, the printing press, and Newton’s laws of motion; second, how remarkable the growth since 1800 has been. So why not for 500 years? And then, why during the last 200?

Mokyr explains that two things must be present for continual benefits to accrue: 1) the development of an advancement paired with 2) an understanding of why it works. For example, hand washing during childbirth was recognized as leading to lower maternal mortality, but the practice was not adopted until decades later when Germ Theory explained why. Innovation must go hand-in-hand with understanding for advances to build upon each other in a useful (i.e. economic) way.

The environment in which these innovations land, Mokyr notes, is also important—since new technologies often replace the old, a society needs to be open to change. The risk is that those of the establishment feel threatened and block progress. Aghion and Howitt’s contribution was creating an economic model for the process of the new destroying the old. If this is what drives growth, what is the right amount of “creative destruction” that makes business ventures worthwhile while rewarding newcomers? What kinds of institutions do we need—for R&D, for workers—to support that equilibrium?

It is no accident that the Academy is awarding this Nobel now, as AI-related innovation enters the mainstream. Keep in mind, too, that economic growth is not only measured by wealth per capita, but also the level of healthcare and education, the quantity of leisure, and quality of products. AI promises progress on all those fronts, but what world is here to meet it?

The long view reminds us that innovation alone does not guarantee progress in quality-of-life measures. Now, maybe what has emerged from the complex interaction of science, technology, and society post-Industrial Revolution represents a new phase. Maybe we have outgrown the old mode and flourishing is more assured. Maybe we will continue to have strong institutions supporting honest scientific inquiry, where vested interests do not have the last word, and where the market force of creative destruction trumps incumbents. Maybe that is the environment in which this transformative AI technology is landing.

But if that narrative rings even a little hollow, this year’s Nobel Prize asks us to remember history, check in on society’s institutions, and not take progress for granted.