Companies are struggling to cope with rising wage costs. As reported in recent earnings calls, this fact seems to be true regardless of whether you are a firm trying to attract and retain hourly workers or highly paid software engineers. In some cases, the labor shortage is having an immediate impact; restaurants like Starbucks have curtailed hours in certain locations due to COVID-related labor shortages. Other firms, like Boeing, are adequately staffed today but remain deeply worried about finding the high-skilled talent needed to meet future production schedules.

Whether this condition persists or fades away depends both on how we got into this dilemma and what actions we might take to get out of it. Escalating wages today are largely the result of two forces: First, the record-breaking fiscal and monetary policies enacted during the pandemic fueled demand for a wide range of goods. Second, the labor force failed to draw in enough workers to meet this surge in demand. The negative impact of COVID on employees’ ability and willingness to work is obvious. But other factors behind the drop in the labor force participation rate (early baby boomer retirements, lack of affordable childcare etc.) are at play. Employers’ success in pulling these more reluctant workers back into the labor force will greatly influence how long wage inflation lasts.

There is some evidence that labor markets are already adjusting. A total of 467,000 jobs were added in January of this year, and estimates of the number of jobs added in November and December were revised upward by 709,000. But the labor force participation rate (the number of Americans either working or actively looking for a job), at 62.2% remains below the 63.4% level established before the pandemic. Women, with a participation rate of just 56.8% today, have been particularly reluctant or unable to return to work.

Companies are doing some interesting things to cope with the worker shortage and demand for higher wages. Many are offering more flexible work arrangements to attract talent. In manufacturing and distribution industries, companies are turning to technology (think robotics) and a range of other labor-saving techniques to replace high-cost labor. Finally, in the technology sector, where the war for programmers is particularly acute, companies are increasingly buying competitors as a means of filling the talent gap.

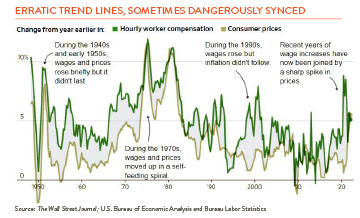

Whether you consider today’s wage gains a positive or negative largely depends on your political viewpoints. Many on the left, believe that these higher wages are long overdue — labor’s share of national income has only recently started to inch up after falling steadily for decades. Those on the right point to the risk that higher wages could fuel more general inflation as employers pass those costs on to customers in the form of higher prices. This risk is particularly acute when inflationary expectations become entrenched and lead to a “wage-price spiral.” As the chart above shows, the relationship between hourly compensation and consumer prices, while not perfectly in sync, is close enough to be a concern.

There are many reasons to think we may yet avoid this form of destructive price cycle. Labor’s bargaining power, while growing, is not what it has been in past periods of high inflation. The deflationary impact of globalization (generally the ability to substitute higher cost domestic goods with lower-cost imports) remains strong, and technology has made it easier for firms to replace workers with labor-saving machines. Importantly, investor expectations of future inflation, as measured by the yield spread between Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) and similar maturity Treasuries, remains muted. This metric suggests that investors still have confidence in the Fed’s ability and resolve to control rising prices. Maintaining that confidence will be just as important as any possible future policy implementation. Let’s hope it holds.