In 2020, as the globe was grappling with the first chaotic year of the pandemic, The New York Times ran a feature on a small shop in Kyoto, Japan called Ichiwa that had been operating for over a thousand years by selling the same toasted mochi it always had. The pandemic had reduced visitors to a trickle, but having withstood centuries of wars, plagues, and disasters, Ichiwa was not terribly worried about its finances or the course of its business. “Like many businesses in Japan,” the Times went on, “Ichiwa . . . takes the long view – albeit longer than most.”

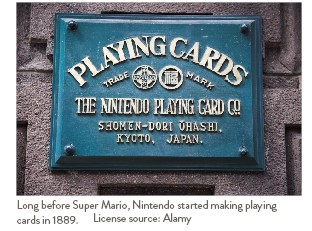

Long view indeed. Japan, you may well know, is a champion of very old businesses that have been operating continuously for 100, 500, or sometimes 1,000 years. Called shinise or “old shop,” they often are small family-run operations in food, traditional crafts, or hospitality that focus on doing one thing extraordinarily well. A handful also have grown larger – like Nintendo (1889), Suntory (1899), and Kikkoman (1917). In 2020, one Japanese research institute reported that Japan had over 33,000 businesses that were at least 100 years old, over 3,000 that were over 200 years old, over 140 that were over 500 years old, and over a dozen in the 1,000-year-old area.

As bastions of stability, shinise businesses are always a fascination, but especially so in times of anxiety and crisis. How do they keep going even at times the world seems to be falling apart?

For one thing, they prioritize resiliency and longevity above all else. Almost across the board, they have no debt and hold ample cash reserves – sometimes enough for two years. They keep capital investments modest. They forego expansion or growth opportunities that might threaten business continuity. Also, they adhere to core values across generations and take pride in high levels of craftsmanship.

In a 2023 study, McKinsey found that publicly traded family-owned businesses outperformed their non-family-owned corporate peers in shareholder return. They were more resilient, more adaptable, and had four mindsets in common that contributed to their success: 1) a focus on purpose beyond profits, 2) a long-term perspective combined with reinvestments back into the business, 3) financial conservatism and caution about debt, and 4) good internal processes for efficient decision-making.

These characteristics are very reminiscent of the shinise. Many operate by kakun or foundational family precepts that guide decisions. Often, these address treating employees well, supporting the community, and making the highest quality products – which in a way, makes these very old Japanese companies the pioneers in sustainability well before “sustainability” was a thing.

Of course, being so conservative also means that being innovative is neither a characteristic nor a priority. Shinise businesses are the polar opposite of the “move fast and break things” ethos of 21st century tech. Overreach is seldom an issue, and some may even think these businesses are a bit too frozen in time. For example, The New York Times reported that Ichiwa had recently turned down an offer from Uber Eats to branch into delivery.

But thinking in terms of centuries rather than quarters does change the calculus of decision-making. The point is, if stability is the priority, there are practices to follow even when surrounded by chaos: conservatism, ample reserves, debt avoidance, and sticking to your principles and core work. Also, you can take the long view – sometimes, the very long view.