In an earlier edition of the newsletter, we reported on a study done by the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research. They found that the age at which financial mistakes are minimized is on average age 53 or 54. This means we stumble through a lot of financial errors from high school to near retirement. Wouldn’t it be much better if we learned the important financial lessons early on, so we didn’t suffer so many painful financial losses later?

Well, progress is being made. Eight years ago, Hanson & Doremus was asked by the Grossman School of Business at the University of Vermont to start a ‘Personal Finance’ course, open to business majors as well as students from across the campus. Art Wright and I have taught this course every semester since, with enrollments always at the maximum.

And momentum is building to introduce financial literacy to even younger students. This is important since college student debt has increased from $500 billion in 2007 to $1.6 trillion in 2024, and average credit card debt of 22-24 year olds, according to Experian, is $3,300 today, up nearly 50% from ten years ago. Finance is becoming a serious and expensive business for every young person now.

According to The Economist, 26 states (including California as of this summer) have now mandated a financial literacy course as a requirement for high school graduation. Within the next five years it is estimated that 70% of all high school students will live in a state requiring a financial literacy course.

Here in Vermont, John Pelletier runs the Center for Financial Literacy at Champlain College, which was established in 2010 to offer instruction to teachers of K-12 financial literacy and to monitor national progress in financial literacy programs. I asked John what he thought were the three most important financial lessons young people need to learn.

First, he said, they need to understand what makes up a credit score and how to ensure their score is as high as possible. Most young people have no idea what a credit score is and don’t realize that their score is a key factor in determining how much they pay for a mortgage, car insurance, borrowing for a consumer purchase, and whether they will qualify for a credit card.

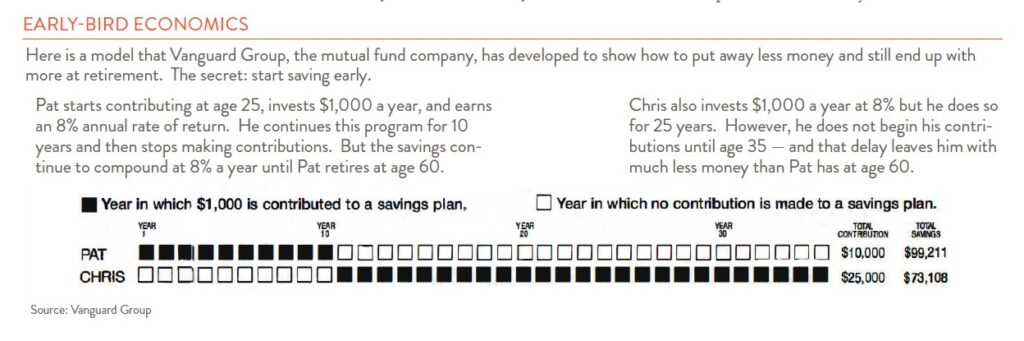

A second important lesson is to understand compound interest, the idea that you earn interest on your initial investment and also on the interest previously earned. Warren Buffett says compound interest is like a snowball rolling down a hill. It picks up more and more snow until it becomes very large at the bottom. We used the Vanguard chart shown below in our January 1997 newsletter. It is as valid today as it was then. The person who invests early (Pat) actually ends up with more money at retirement than the person (Chris) who invests two and a half times more but starts saving 10 years later. The early bird here does indeed get the worm.

And the final lesson is understanding budgeting, learning how to spend less than you earn. John suggests two books for young people on how to budget and accumulate wealth. The first is David Bach’s, The Automatic Millionaire. Most people will not sit down and write out a monthly budget, listing all their income and then all their expenses. It’s too tedious, and most of us don’t have the discipline to stick to a budget anyway. The better approach, according to Bach, is to “pay yourself first,” set aside what you want to save, and then shoehorn your spending into what is left. It’s still painful and difficult but it’s an approach more likely to succeed.

John also recommends Chris Hogan’s book, Everyday Millionaires, which studied over 10,000 millionaires to find the secrets to their financial success. According to Hogan, it boils down to strong habits, a determined mindset, and strategy. The common denominator is millionaires save consistently, they avoid debt, and they invest the maximum in their retirement plans to take advantage of compound interest. Paraphrasing Warren Buffett again, investing (and wealth accumulation) is simple, but it is not easy.