From the end of the Civil War to 1914, globalization, or the increase in trade between nations, grew dramatically. This was due in part to leaps in transportation technology like steamships, the building of the Suez/Panama Canals, and transatlantic cables which allowed for more direct telegraph links. Then came World War I, and globalization came to a screeching halt. The war involved the most important economies in Europe, slashed economic activity, and encouraged beggar-thy-neighbor trade policies.

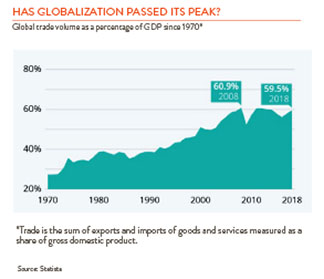

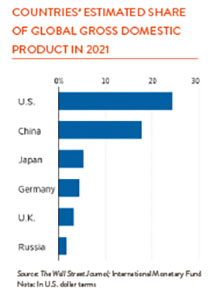

Today many wonder whether the current era of globalization, which began in the late 1980s, will also end abruptly. If it does it will not be due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Russia is a small part of the world economy, much smaller than Germany/France/England were prior to 1914, and although Russia is important in energy and some commodities, it is not a major factor in global supply chains.

No, if globalization comes to a halt, it will be due to politics. Here in the U.S., Democrats (the supporters of labor unions) have blown hot and cold on globalization, liking the increase in trade but assailing the loss of jobs to lower wage countries. The Republican party has historically been the party of free trade and low tariffs, but this took an abrupt U-turn under President Trump. The Republican agenda now includes resistance to globalization, limiting immigration, and securing the southern border.

So, we may be in for a period where both political parties are critical of globalization and more supportive of tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers. The political winds are shifting. J.D. Vance, author of Hillbilly Elegy, is running for the Senate in Ohio as a Republican. Originally opposed to Trump, he is now an ardent supporter speaking out about excessive federal subsidies to the poor which he says lessen the incentive to work, and about the loss of jobs to globalization.

So, will this era of globalization end soon? We are doubtful. The world is too interconnected today, and too many businesses depend on foreign sales and production. What is more likely is that reliance on one country will be replaced by multi-country sourcing. Some production in China may be shifted, say to Vietnam or Indonesia, and production in Vietnam or Indonesia might be shifted to Mexico, and so on.

Some production will be “re-shored,” shifted back to the U.S., but the process will be slow and uneven. Intel and others are making a concerted effort to ramp up semiconductor production here and move away from South Korea (Samsung) and Taiwan (Taiwan Semiconductor). A recent WSJ article highlighted how Salomon SAS is trying to bring the manufacture of hiking boots back from Asia to France. The re-shoring is going slowly as the supply chain in Europe must be rebuilt from scratch. Adidas of Germany tried setting up highly automated shoe production lines in Germany and Atlanta in 2016. Both plants were shut down in 2020 as uneconomic. New Balance still manufactures some of its shoes here in the U.S. but can only source 70% of necessary parts locally.

Re-shoring sounds like the answer to many prayers but re-shoring does not generally involve big employment gains. Salomon’s highly automated boot factory will employ just 15 workers versus five times this number in Asia.