Since the summer of 2021, housing affordability has declined at the sharpest rate in 25 years. The situation has not gotten any better recently.

Affordability can be estimated from three moving parts: mortgage rates, home prices, and household income. A common way to think about it is how much of your monthly income is eaten up by housing payments. In mid-2021, affordability was great. Mortgage rates were under 3 percent, and in Vermont the median home price was $230,000 and the median household income was around $75,000. That works out to a monthly payment of around $1,400 (including estimates for taxes and insurance), or 22 percent of income. That all changed with higher rates and higher home prices.

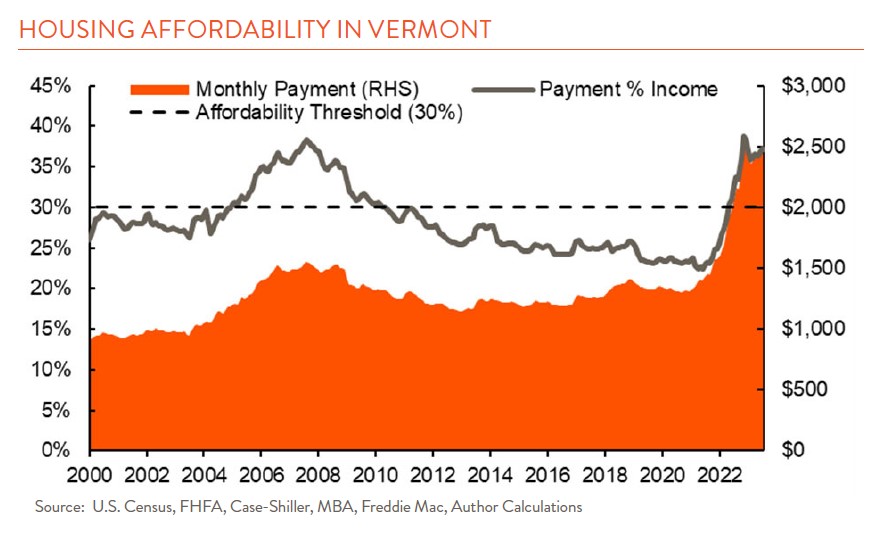

Fast forward to the end of last year, and mortgage rates had shot up to 7 percent while the median home price in Vermont increased to $310,000! In just a year, monthly payments climbed by over $1,000, to $2,500 per month. If we extrapolate Vermont income from national wage growth figures, the median household may now be making closer to $80,000. Unfortunately, that increase does little for affordability.

The chart illustrates the dramatic increase in monthly payments, shown both in current dollars and as a share of income. The Department of Housing & Urban Development considers 30 percent of income the threshold for affordability, and the current figure for Vermont is well into unaffordable territory at 37 percent. The only comparably unaffordable period over the past 25 years occurred in 2007 at the peak of the housing bubble. National figures reflect similar trends – the Atlanta Fed’s latest estimate of housing payments as a share of income at the national level is 40 percent.

Some observers had hoped–from an affordability angle–that higher mortgage rates would dampen demand, allow supply to catch up, and help take some of the steam out of the housing market. While there was a dip in home prices at the beginning of 2023, they’ve come back during the summer moving season. The main culprits seem to be lack of inventory and low housing turnover.

The pandemic saw labor shortages that made it difficult for homebuilders to find workers and supply chain disruptions that led to much higher materials costs. On top of that, work and lifestyle changes drove shifts in housing consumption patterns we have yet to fully understand, posing new challenges for local developers. The result was a few years of acute underbuilding on top of more chronic underbuilding since the housing market crash in 2008.

Not only have not enough homes been built, but higher mortgage rates have also “locked in” the throng of borrowers who refinanced at 3 percent and now balk at the monthly payment if they move and assume a 7 percent mortgage. That has made them much more likely to stay put, which keeps homes that might otherwise be for sale off the market.

So what needs to happen for things to get better? Both here in Vermont and nationally, we need to see some combination of more houses built, lower interest rates, and higher incomes. None of those things tend to move very quickly, with the exception of interest rates at times. However, despite assurance from some real estate agents that borrowers will be able to refinance in a year or two “once interest rates come down,” the future path of mortgage rates is not at all clear. For more on what’s in a mortgage rate, see last month’s newsletter.

There is one type of homebuyer who is less affected by these trends: the all-cash buyer. While they do have to contend with higher home prices, they do not have to face 7 percent mortgage rates. These buyers are not necessarily the wealthy buying second homes. They may be retirees who have saved their whole lives or can fund the purchase of one home with the sale of another. That leaves younger first-time homebuyers the ones feeling the pain most acutely.