How worried should we be? The list of potential investing headwinds is growing. The economy looks like it’s decelerating as the Delta variant, supply chain constraints, and hiring challenges throw sand in the cogs of growth. Inflation is running hot. Some are even talking about stagflation, the combination of low growth and high inflation that plagued the 1970s. Throw in climbing oil prices, energy shortages in Europe and China, and rising great-power geopolitical tensions, and you may indeed think you’re back in the 1970s.

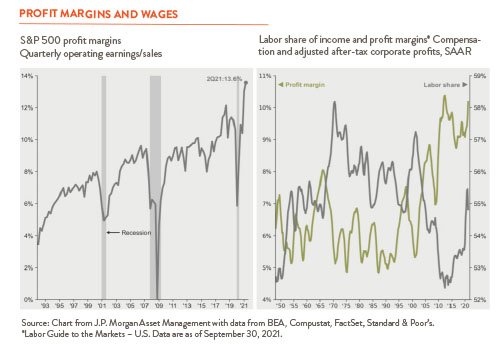

All this is happening as we enter an earnings season wondering if earnings and margins finally have peaked. Analysts have raised their earnings estimates the last five quarters, and companies have beaten them the last four. And as the first chart below shows, profit margins are at an historic high. While companies have been able to keep up with rising input costs and labor shortages so far, things won’t be easy if these challenges persist.

The period of easy earnings comparisons is over. But saying that easy times are over is not the same as saying that doom is imminent. We don’t think it’s time to panic yet.

Still, there are two things we can’t help thinking about. One is whether labor markets are changing in ways we haven’t yet fully fathomed. Workers have been quitting or choosing not to return to work in surprising numbers, and the common thinking is they will come back when they feel safe and well compensated — a matter of time. But what if worker demands and labor markets are changing in more profound ways? The second chart above shows that workers have not won much of the last decades’ rising corporate profits, and they may demand more.

The other thing has to do with inflation. Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff recently wrote in Project Syndicate that we tend to see inflation “as a purely technocratic problem” that central bankers can solve by applying the brakes or revving up the gas. If that’s the case, there’s good reason to think inflation is “temporary” rather than “persistent.” But, he says, long-term inflation also has roots in “political economy” problems — geopolitical challenges, demographic aging, and sharply rising government debts. Those aren’t easy fixes. Likewise, economist Nouriel Roubini has suggested that deglobalization, balkanization of supply chains, cold wars, aging populations, tighter immigration rules, and climate change all are possible contributors to sustained inflation.