When first introduced, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) were considered a novel improvement to the existing passive mutual fund structure. In addition to tracking a stated market index, ETFs allowed investors to trade at market prices throughout the day. Up until then, standard mutual fund investors had to settle for trading at only end of day prices. This instantaneous pricing was particularly important for large, institutional investors executing sophisticated trading strategies. The subsequent steady inflow of money into ETFs created something of a flywheel effect with growing asset bases leading to steady declines in fund level management fees. Financial service firms, sensing opportunity, rushed to get in on the game. Between 1993 and 2009, the number of ETFs increased 10 times to over 1,000 funds and by 2020, more than 7,100 ETFs were being traded across the globe.

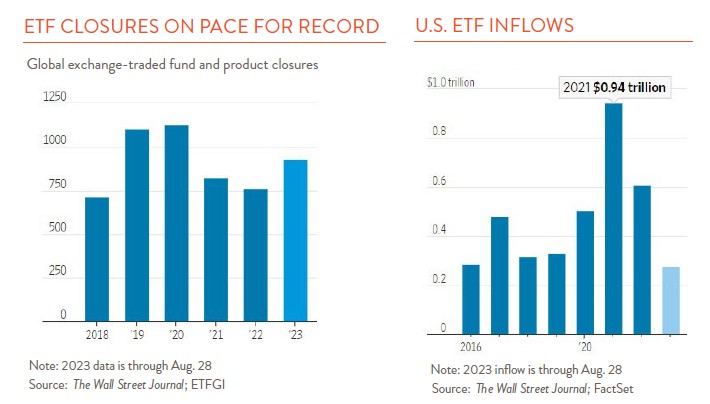

Now, after more than 30 years of steady growth, an interesting thing is happening. While the number of ETFs continues to increase on a net (openings vs. closings) basis, the pace of fund closures is accelerating. So far this year, a total of 929 ETFs have closed globally, a marked increase from last year’s 373 YTD closures. More importantly, the amount of money flowing into ETFs is also falling. U.S. ETFs have attracted $275 billion so far this year, a level well below the $605 billion recorded in all of 2022 and the $942 billion logged in 2021 (see charts below).

At least three developments are contributing to this sea change. The first has to do with industry structure. Issuing ETFs is a scale business. Most big ETFs are essentially identical (one S&P 500 ETF is just like another), so investors are attracted to those with the lowest fees. Further, the cost to manage these funds are relatively fixed, so the more money you manage, the lower the fee you can charge. This reality has led to consolidation in the ETF business. Consider that while over 160 firms issue ETFs today, three firms – Blackrock, Vanguard, and State Street – hold almost 80% of the invested assets.

Second, for years ultra-low interest rates caused many investors to turn to riskier stocks to boost return. This “there is no other alternative or TINA” trade presented a favorable backdrop for financial firms interested in issuing the next, best stock ETF. Now, thanks to higher interest rates, investors can turn elsewhere to find attractive returns with much less risk.

Finally, product proliferation can be blamed for the tempered enthusiasm for ETFs. The largest ETFs today track broad market indices like the S&P 500 or the MSCI EAFE. But as these products have matured over the years, ETF issuers have expanded into niche strategies. Today, for example, you can buy ETFs targeting just about every part of the investment market. More complex (read riskier) strategies employing leverage and hedging are also common. Thematic ETFs designed to track an optimistic investment narrative, such as Cybersecurity or Artificial Intelligence, too have proliferated. To get a sense of how far the “thematic ETF” concept has gone, consider that recent closures have included a fund that invests only in companies headquartered in Texas and one focusing on Dermatology and Wound Care.

The track record of thematic ETFs in particular deserves attention. Expressing an investment theme through individual stock selection can be difficult – often only a limited number of firms operate in the target market, or the companies also have other business lines. Fees too can be high when the ETF fails to attract sufficient funds. Finally, poor performance is common. Typically, by the time an investment theme is well known, and the fund launched, the prices of the constituent stocks already reflect the perceived good news.

ETFs tracking broad-based indices at a low cost represent a true product improvement. But investors should carefully examine the fees and underlying structure of funds in more niche areas of the ETF market. Often what seems like a good idea in the investment world is anything but.