The 401(k) has become a retirement savings institution—over half of civilian workers have one. But the government might not want to keep paying for the advantaged tax treatment it currently allows.

For some quick context, 401(k)s are a “defined contribution” plan, where the employee contributes x% of salary in the current year and the employer often matches up to a certain amount. The plan comes with a tax advantage: contributions are made with pre-tax income, and taxes are deferred until funds are withdrawn in retirement, usually when individuals are in a lower tax bracket.

The favorable tax treatment of 401(k)s costs the government in a few ways: 1) tax collection is deferred from the present until retirement; 2) the government collects a smaller percentage of income since retirees are typically in lower tax brackets; 3) the government misses out on taxes that would have been paid on capital gains realized along the way. That all adds up. For 2021, the Treasury valued the revenue it would have earned if not for 401(k)s at $119 billion.

That is a lot of money, around 2% of fiscal spending in 2021, though the government is probably willing to pay for this if it accomplishes its goal of getting more people to save for retirement. But it is not clear that the tax treatment of 401(k)s does that. Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research contends it is more the automatic payroll deductions that induce saving, not the tax advantage.

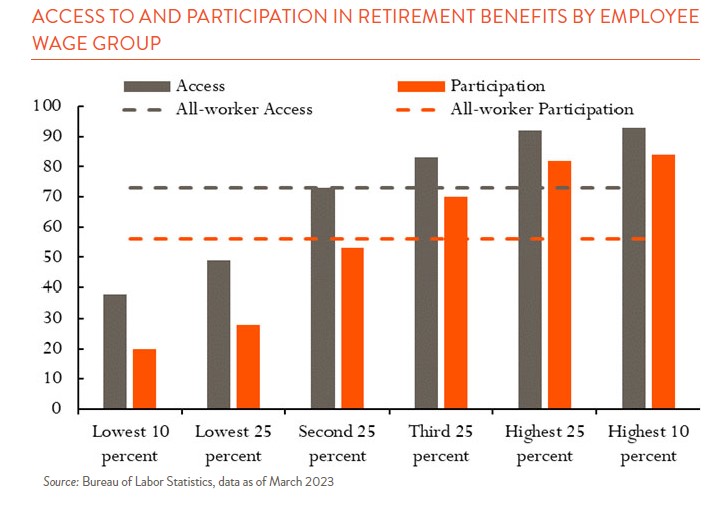

It also probably matters to the government who receives the benefit. The chart below shows retirement plan access and participation both increase with income—only half of the bottom quartile of earners even have access to plans. In other words, the tax expenditure ends up disproportionately benefiting the highest earners. With Social Security’s Trust Fund set to run out by 2033, supporting wealthier workers’ retirement might be an easy target.

The 401(k) is also under fire from some large corporations. In the fall of 2023, IBM announced it would discontinue the 401(k) option and instead reopen its pension. In contrast to the 401(k)’s “defined contribution,” a pension is a “defined benefit” plan, where the employer agrees to pay x% of salary in the future. With pensions, the employer is on the hook to meet that commitment and invests in assets that can achieve the growth it needs. This strategy ran into some trouble in the 2000s from a combination of major declines in the stock market (tech bubble bursting and Global Financial Crisis), and regulatory changes to standards for pension accounting. The result was most pensions were underfunded—the obligation they had built up to their employees was greater than the plan’s assets. Rather than continue to commit to future payouts, many corporations stopped offering them.

With the stellar returns of the past decade, more pensions are out of the hole and are now overfunded. Such is the case with IBM, and it wants to get at that money. By reopening the pension, IBM can lean on the assets it has already built up to fund the benefit to employees, instead of contributing cash to 401(k)s today. This option is not available to all corporations—they need to have an old pension plan that has grown to overfunded status as well as a desire to change the benefit they offer employees.

Like 401(k)s, many pensions are also tax-advantaged, and the government may not be so keen on them either. So what should we do if tax-advantaged retirement savings becomes a thing of the past? Keep saving. Employers would probably still provide some form of contribution towards retirement, and we should take advantage of any “match” offered. Ideally, “pay yourself first” by setting up the contributions to move automatically from paycheck to account. An added nudge toward retirement savings with 401(k)s is the penalty for early withdrawal (before reaching retirement age). If that goes, the discipline will fall to us to make sure we do not tap into those assets. The bigger picture is that regardless of the investment vehicle we should still make sure we are setting aside money for retirement.