Standard economic theory holds that rising demand leads to higher prices and falling demand, lower prices. When supply exactly matches demand, a “clearing” price or fair value is reached. In the real world, however, things do not always work out this way. In some cases, prices fail to adjust to shifting supply and demand because consumers lack the information they need to make rational decisions. But sometimes, other, more psychological forces can influence how prices are set.

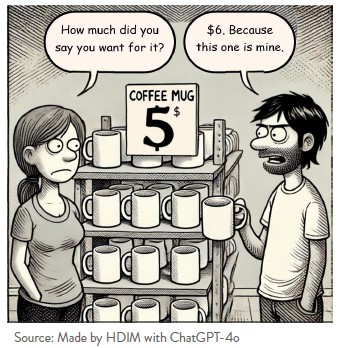

Back in 1990, behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler found that something called the endowment effect could also influence price adjustments. Their work included a study in which Cornell students were asked to buy and sell coffee mugs. Half the students were given mugs for free, and they were paired with students who weren’t given mugs to find a fair price. But buyers and sellers could not agree. While standard economic theory would have predicted a mutually agreeable price in most instances, sellers demanded approximately twice the amount as buyers were willing to pay, and most trades did not get done. In other words, the students who received a gifted mug assigned a higher value to it simply because they owned it.

The endowment effect is one manifestation of what Kahneman identified as loss aversion, or our tendency to experience the pain of loss much more than the joy of gain. Loss brings outsized regret, and we have a bias toward maintaining the status quo and not giving up our position.

Other research into price setting has suggested that the endowment effect results from the different ways in which buyers and sellers establish their price estimates. To avoid paying for more than an item may be worth, buyers will anchor on the lowest available price estimate. To maximize profits, sellers will focus on the highest available estimate when establishing a price. The resulting gap can gum up pricing in otherwise rational markets. While these cognitive biases likely play a role in all price-setting, they can become particularly pronounced in cases where there is more uncertainty as to the true value of the item in question.

While the above research may seem esoteric, the behaviors associated with the endowment effect are all too familiar in many markets today. Consider the market for Taylor Swift concert tickets. In a Wall Street Journal column last month, James Mackintosh reported that tickets for Swift’s Eras Tour were changing hands at well over $1,000 each or more than eight times face value. In an informal survey, he found that most existing ticket holders would be unwilling to pay the going rate because they felt it was too high. Irrationally, however, they also felt that the same elevated prices were insufficient to convince them to sell.

The endowment effect can lead to many unhelpful behaviors. The residential real estate market is, in many ways, quite different from the market for mugs discussed above. Price discovery is complicated by the fact that each house is unique, and transactions are typically emotional in nature. But the endowment effect also helps complicate the transaction process. This is especially true in weak markets, where sellers are reluctant to drop prices and sales cycles become extended. In the investment world, to avoid the pain associated with loss, individual and professional investors alike often hang on to losers too long and sell winners too early. This can be particularly harmful given research which shows that stocks tend to experience price momentum over time. And in markets prone to volatility, the endowment effect can cause a “high water mark” problem where asset holders avoid selling as they anchor on past high valuations that may no longer prove realistic.

What can asset owners do to avoid falling prey to this cognitive bias? The best first step is to recognize situations where it may be present. Seeking out one or more objective valuation opinions or an “outside view” can also help identify when your expectations are overinflated. In our stock research work, for example, we often rotate research responsibilities among analysts to combat this very natural human tendency. Finally, reminding yourself of the “opportunity cost,” or how else you might invest your funds, can also be helpful.