Social Security’s fragile state is hardly news. Its Trustees’ most recent annual report issued back in March 2023 showed that the Social Security Trust fund (technically the OASI fund which backs retirement but not disability benefits) will run out of money by 2033. While this is certainly not good news, it is important to point out that this does not mean that all benefits will cease at that point. To understand why, let’s consider how the program is funded.

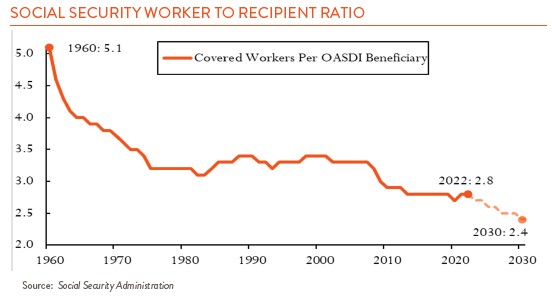

Social Security, first established in the 1930s, was designed as a “pay-as-you-go” system with taxes on workers covering retiree benefits. This approach made sense at a time when the ratio of workers to retirees was high. But declining birth rates in the post-WWII era and rising life expectancies significantly affected that relationship (see chart below). Enhancements over the years, such as the extension of benefits to dependents and survivors, weighed further on the program.

Over time, these forces caused the growth rate of fund outflows to exceed the growth rate of fund inflows. Trustees began dipping into fund assets to meet benefit payments in 2021 and have since been slowly whittling away the Trust fund’s balance. When it is depleted, however, this does not mean the plan is bankrupt – ongoing payroll taxes and taxes on benefits should be sufficient to cover anywhere between 70%-80% of expected payouts for the next 75 years. Maintaining the promised level of benefits at that point will require a big increase in taxes, a reduction in benefits or, some combination of both.

So what is the likely path forward? Significantly reducing benefits seems unlikely given Social Security’s overall importance to most American’s retirement funding needs. Approximately 67 million people receive Social Security each month and for 40% of recipients, the payments represent more than half of their total income. Most polls too show broad public support for solving Social Security’s funding problem with a preference for paying more (i.e. raising taxes) rather than cutting benefits.

Solving Social Security’s funding challenges will require making some difficult decisions, so we are unlikely to hear much about solutions during this election year. But hundreds of remedies have already been proposed. Here are several that could be part of a an ultimate solution:

To Raise Revenue:

- Raise or eliminate the Social Security wage cap. This year Social Security levies taxes (6.2% or 12.4% if you are self-employed) on wages up to $168,600. Eliminating this wage cap altogether or increasing it to a specific amount such as $250,000 or $400,000 has been proposed numerous times.

- Broaden the kinds of income subject to Social Security taxation. This might include investment income, estate proceeds or gifts.

- Expand the taxation of benefits. Today, lower income Social Security recipients do not pay tax on their benefits. Expanding the tax to all recipients or increasing the rate at which they are taxed is possible.

- Gradually raise the payroll tax rate. This option spreads the cost over a wide range of workers but is generally not popular.

To Reduce Benefits:

- Lower the inflation rate applied to annual Social Security benefits. Today the CPI is used to make annual inflation adjustments. Replacing the CPI with another metric such as the “chained CPI” would likely lower benefits over time.

- Gradually increase the full retirement age. This is not a popular option with workers today but Congress solved Social Security’s last (1983) funding challenges by raising the eligibility age from 65 to today’s approximate 67 level.

Despite its obvious challenges, Social Security is not going away. But achieving consensus, particularly in today’s divisive political climate, will take time. This is unfortunate as arriving at a solution sooner rather than later would distribute the impact over a larger number of workers and allow those most impacted (likely younger and wealthier workers) to prepare for the future.