When I started in the investment business back in the early 1970s, global investing meant looking at a few markets in Europe (mostly London), the Asian market, but limited to Japan, and for the truly adventurous, buying a few British trading firms in the infant Hong Kong market. Today, there are thriving financial markets everywhere including Shanghai, Mumbai, Sao Paulo, and Dubai. The reason for the growth is globalization. The world economy has become much more interconnected and interdependent in the last four decades. Products or parts of products are made in one country, sent for processing or assembly in a second country, and sold in a third country.

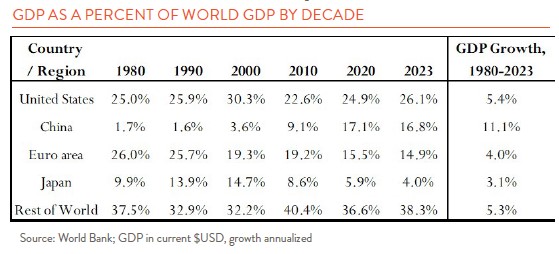

Aswath Damodoran, a global investment commentator and Professor of Finance at NYU’s Stern School of Business, dates the take-off of the current iteration of globalization to the early 1980s. The biggest winner has been China. Its share of global GDP has grown dramatically, especially since 2000 (see chart below). Consumers worldwide have benefited from the greater variety and lower price of goods. Global institutions such as the World Bank, IMF, EU, and NAFTA have gained power through market rule setting. And, as mentioned earlier, financial markets have grown to supply financing for global trade.

On balance, Damodoran thinks globalization has been a net positive, but proponents have failed to acknowledge the costs and the number of losers. Japan and Europe have lost share in the global economy, and consumers have lost control of many markets. In food production, local produce has been swamped by cheaper and more readily available global supplies. Small businesses have lost share to global companies, which can move production quickly to gain price advantage. And blue collar workers here in the U.S. have suffered as more production has moved offshore. The number of manufacturing workers in the U.S. has declined from 20 million in 1979 to 13 million in 2024.

Whereas Damodoran sees globalization as a net positive, President Trump sees it as a distinct negative. For him, foreign countries and companies have been eating our lunch for nearly five decades now. We need to charge foreigners for access to the world’s largest market, and tariffs do just that. Not only will these charges bring in significant revenue, but they will also bring back jobs and rebuild towns and factories decimated by globalization.

But is this all just nostalgia for the 1950s, when American workers built products in American factories for American consumers, or is this the start of the rebuilding of America’s production base? Regardless, it is important to remember that America has been a major beneficiary of globalization. America still produces one quarter of everything produced in the world. This does not include foreign production by U.S. companies, such as Nike’s production in Asia. And we do this with just 4% of the world’s population. Impressive.

It would be nice if the announced tariffs (extreme in some cases) were just a ploy to get countries to the negotiating table. It certainly is true that America has suffered from many foreign tariff policies and restrictions. China, for instance, dragged its feet on allowing Visa and Mastercard into the country until its national champions Alipay and WeChat pay could gain dominance. Now foreign credit card companies must work through Chinese companies if they want access.

Thomas Friedman, the columnist on global issues in The New York Times, has an interesting idea for how to start balancing our trade, especially with China. In the early days of globalization, China invited American companies to set up factories using Chinese workers. This led to export gains as well as knowledge of cutting edge production methods.

What if America did the reverse today? “Made in America, by American workers, in partnership with Chinese Capital, Technology and Experts.” We could invite foreign companies with their advanced manufacturing systems to produce in America in joint venture with American companies and using American workers. Think Chinese EVs, solar cells, container ships, machine tools – whatever – made here in America with both foreign and American involvement. Supply chains would slowly return to our shores and trade deficits would decline. Quite exciting but it involves a lot of government trust and cooperation, on both sides. Unfortunately, trust is something that is sorely lacking today.