The Wall Street Journal recently reported that two Chinese semiconductor foundries just went under and now are among the nation’s six failed chip making projects the last three years. China has thrown billions into building an independent semiconductor industry, but it hasn’t been easy. Throwing money at the problem hasn’t been enough.

Everyone knows China wants semiconductor independence. Semiconductors are strategic, they are in everything, and everyone needs them. Beijing has committed over $50 billion to support the industry since 2014, and local governments have thrown in even more. But China still is far behind – some say a decade or more. Even if China can design advanced chips – and private companies like Baidu and Alibaba are doing just that – being able to manufacture at the leading edge is a different story. The playbook China has used for other industries – invest, access foreign tech (or the more cynical might say, steal) – hasn’t worked here.

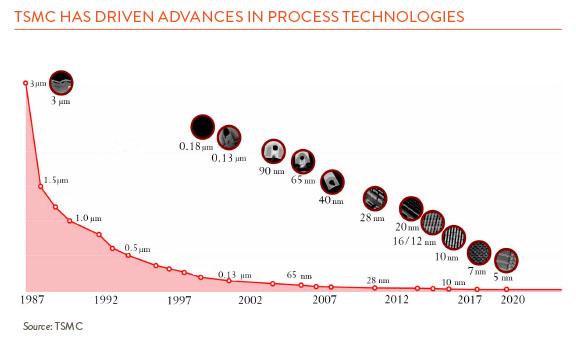

China’s national champion SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation) started up over 20 years ago but announced only in 2019 that it would start making 14 nanometer (nm) chips. Meanwhile, the world leader, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC, is making 5 nm chips at scale and moving on to 3- and 2-nm. Samsung is hanging in there too. And because each jump in process technology is brutally difficult, money is not all you need. GlobalFoundries, spun out of AMD in 2009, was backed by the United Arab Emirates and had plenty of money, but it gave up at 10 nm in the early teens. It was just too hard, and it was perfectly profitable to hang back and produce less advanced chips.

Never say never when it comes to China, but building a whole semiconductor value chain is hard. You need design skills, manufacturing know-how, and semiconductor equipment to make the stuff. But more than that, you need close working relationships with customers and a collaborative ecosystem, where each part of the value chain works closely with the others.

It has taken four decades to get to the ecosystem we have now, and the amazing thing is that there is value (and margin) in each part of the chain. It starts with designers at places like Apple designing chips on EDA or Electronic Design Automation tools – and there really are only two leading EDA companies now. The chip designers need to collaborate closely with TSMC. And TSMC really needs to collaborate closely with equipment makers like ASML. There are only a handful of major equipment makers in the world now, and they might be considered the true arms dealers in the arms race.

Equipment is a big challenge for China. Trade restrictions keep China from accessing the most advanced equipment, and there is no other place to go. There is no substitute, for example, for what Netherlands-headquartered ASML makes. ASML has a monopoly on something called EUV (extreme ultraviolet) lithography, the process for etching very small patterns onto silicon wafers. It was not easy for ASML to get to where it is, but nobody else now can do what it does. Simplified, its technology involves pulsing molten tin exactly at the right time with a laser thousands of times a second. A series of mirrors and lasers create a light beam that’s small enough to etch lines a few atoms wide. These are not regular mirrors and lasers either – only one private company in the world makes those lasers. And by the way, when ASML succeeded, the other big lithography player, Nikon, gave up and dropped out.

So none of this is easy – but not everyone has to be at the leading edge. The chip shortages that you read about in the newspaper for autos and the Internet-of-Things require much less advanced chips. But the few companies who can do what no one else can are extraordinarily strategic – and that is why China and the U.S. are turning semiconductors into a geopolitical issue.