“Everyone’s health generally declines with time, and sooner or later we all die, so the question we all must answer is how to make the most of our finite time on earth.”

“. . . if you knew you were going to die tomorrow, you’d spend today one way, and if it was two days from now, you would spend today slightly differently – because you’ll still have tomorrow. The same is true for three days from now, four days from now, or 20,000 days from now. . . But when we’re talking about thousands of days – of years and decades – people tend to forget this logic altogether and act as if 20,000 days is the same as forever.”

These quotes, along with the title of this page, come from Bill Perkins’ book Die With Zero to remind us that none of us have forever. We all die eventually. Those of us blessed with long life will certainly see our health diminish, and unfortunately, some of us will face downright misery in our last days.

It’s a grim message, Perkins acknowledges, but also a reality we must embrace if we’re to plan our finances better – and he thinks many of us are getting things all wrong.

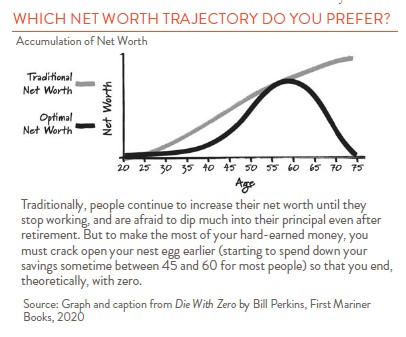

Here’s the thing: Most of us are terrified of running out of money before we die – and we should be because it’s a terrible prospect. It’s why a whole financial planning industry has risen up to address it and why we work hard, save, and prepare for end-of-life medical expenses we hope we never have to pay. But Perkins says many of us take things too far. We save way past the optimal point and die with too much, which is a “terrible waste” because it means we didn’t get to enjoy what we worked so hard for. Instead, what we should be striving for is completely exhausting our wealth and fulfilling the title of his book: to die with zero.

If that strikes you as a crazy and irresponsible idea, hear this out: First, Perkins is very clear that his book is not for the many who struggle to earn enough to save at all. Nor is it for the spendthrifts who live far beyond their means. It is for those who keep saving way past when they should because they are on autopilot.

Second, dying with zero is not about being selfish or forgetting your kids or charitable giving. Instead, Perkins advocates giving while you’re alive, when your heirs and charitable causes are most likely to make the most of your gifts – and because it’s far more generous to give intentionally while alive than to leave a random leftover amount at the random time of your death.

What dying with zero is really about is changing the question from “How can I make sure I don’t run out of money?” to “How can I maximize my enjoyment without outliving my savings?” For Perkins, it’s a question of optimization. You check the mortality tables, count your likely years left, and multiply that times the amount of money you need to live each year. Then you plan your spending by allocating resources to gifting and the experiences you want to have while you’re still healthy enough to enjoy them. And being healthy enough is critical – because most people in their nineties really don’t water-ski much – or do grand trips, attend the Super Bowl, or whatever it is they always hoped to get to someday.

While figuring out how to die with zero can sound like a cold and mechanical calculus, it’s surprising that more of us don’t do it. Perkins says many of us have the best of intentions to spend more but avoid doing so because we hate thinking about the finite number of years we have left. We act like death is never coming. “It’s just some sort of mystery date in one’s future when we expire.” And too many of us see ourselves as staying in our twenties or thirties on an ongoing basis – a fantasy. The consequence is that “We keep putting off wonderful experiences, as if in our final months we can easily squeeze in all those experiences that we had put off all our lives. . . it’s totally irrational.”

Obviously, dying exactly with or close to zero is unlikely for any of us. And perhaps it’s not for everyone. But the concept is really about balancing the present with planning for the future, and as Perkins says, “if we fail to look at our death date at all, we act as if we will live forever – and then there’s no way are we going to get the balance anywhere close to right.” Making sure you don’t outlive your savings is only half the question. “So,” Perkins asks, “what’s the plan for spending down your money so you don’t die with leftover assets and a pile of regrets?”