This week’s release of employment data revealed a tepid labor market. Nonfarm payrolls declined approximately 40,000 over the past two months and the unemployment rate ticked up to 4.6% with both results softer than expected. Investors and policymakers alike will continue to keep a keen eye on future releases for clues as to the nation’s general economic health. While the heightened focus on such short-term measures is understandable, we should be careful not to miss the longer-term trends impacting on the nation’s workforce, particularly the ongoing decline in fertility rates.

America’s falling birth rate is certainly not a new phenomenon. Total fertility has been declining since 1957 when women in the U.S. had, on average, 3.65 children. But as recently as 20 years ago, fertility rates were still hovering around 2.1, or the number considered necessary to sustain a population. The rate has steadily fallen since then and in 2024 it hit a near-historic low of 1.6 children per woman. While there are tangible benefits associated with a smaller population such as less strain on our natural resources, there are also some downsides. A diminishing number of working age adults means less funding for healthcare and retirement programs that have become a key part of the social contract in the U.S.

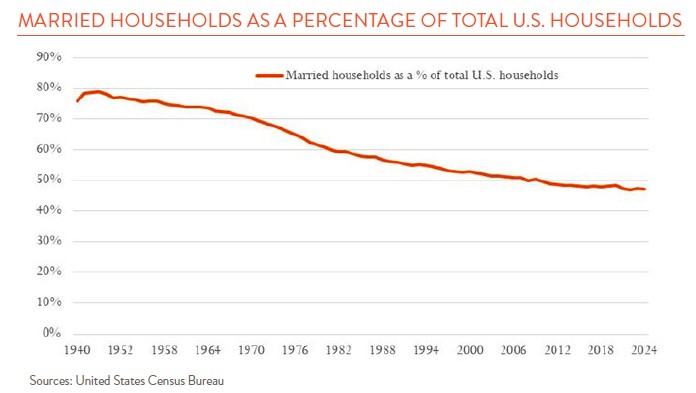

A look into the probable causes of our baby bust reveals some interesting trends. Though fertility rates for married and unmarried women have both declined over time, the rate for married women over the past few years has held at approximately the 2.1 replacement rate. As a result, the drop in overall fertility is due to two factors: a decline in the number of children born to unmarried mothers and, surprisingly, a drop in the number of women getting married. According to a Pew Research Center survey, approximately 25% of 40-year-olds had never married in 2021, a nearly fourfold increase from the 6% recorded between 1960-1980. Race and education also factor heavily in marriage rates. Forty-six percent of 40-year-old Black Americans responding to the survey had not married, compared with 27% of Hispanics and 20% of whites. And those with a high school education or less were nearly twice as likely to be “never married” as those with a bachelor’s degree.

So why are Americans marrying at lower rates today than in the past? Historically, blame for this trend has centered on things like the broad adoption of contraceptives in the middle of the last century, rising education levels of women and high divorce rates. A recent article in The Economist adds to this list by suggesting that technology may be contributing to the decline in marriage and “coupledom” more generally. The rising use of social media, the authors suggest, may be causing unrealistic (read: too exacting) expectations for future partners. Dating apps which allow participants to put their “best self” forward, whether accurate or not, may be Exhibit 1 in this line of reasoning. The increasing amount of time spent online, and reduced time spent in direct, in-person interaction may also be a factor. According to the article, 15–24-year-olds today spend 25% less time hanging out in person than they did ten years ago while the amount of time spent gaming has increased by 50%. The growing adoption of dedicated AI-companionship apps, such as Character.AI, could only further exacerbate this trend.

Reversing the trends of declining fertility and marriage rates will not be easy. A wide range of countries across the globe experiencing similar problems have attempted to do so, with negligible effect. But we should remember that demographics are not always destiny. A smaller domestic workforce could become a more productive one with the help of new technological (yes, AI) and process improvements. A return to more pro-immigration policies could boost our labor force numbers. It is also possible that current forecasts of population decline simply turn out to be wrong. The Zero Population Growth (ZPG) movement of the 1960s, after all, was spurred on by predictions of explosive population growth that never materialized. But if current trends hold, economic growth in the U.S. will have to rely less on growing numbers of native-born consumers and more on everything else going forward.