This is a meditation on reading — deep, immersive reading, preferably of books, essays, or other thoughtful pieces. Not scrolling on your device. Not scanning for news. Not what might be euphemized as “research,” where your eyes flit here or there as you search for the correct spelling of Albania’s capital, the growth rate of the Euro region, or how long the Covid booster’s protection lasts.

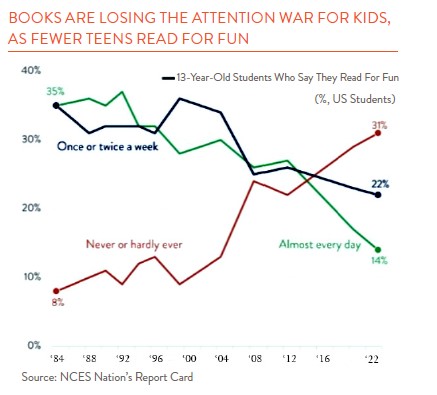

Deep reading for the sake of reading is something we do less of today, as the chart on this page shows. Young people are incredibly adept at finding information in seconds – but apparently, less apt to lose themselves in books. Ask a young person a question, then watch her thumbs fly on her phone to produce an answer before you blink twice. But don’t expect a passionate discourse upon the books that have changed her.

In contrast, consider Joseph Campbell, the professor of comparative literature and expert in mythology best known for writing The Hero with a Thousand Faces. During the Great Depression, when Campbell couldn’t find work (as many couldn’t), he retreated to a cabin in Woodstock to read all day – and he did so for five years. He eventually got a teaching post at Sarah Lawrence College, but he always was a maverick.

“I would get nine hours of sheer reading done a day,” Campbell said of that time. “And this went on for five years straight. You get a lot done in that time. . . Reading what you want and having one book lead to the next, is the way I found my discipline.” He continues: “When you find a writer who really is saying something to you, read everything that writer has written, and you will get more education and depth of understanding out of that than reading a scrap here and a scrap there and elsewhere. Then go to people who influenced that writer, or those who were related to him, and your world builds together in an organic way that is really marvelous.”

For a more recent but quite different example, consider Bill Gates’ one-week reading retreats, which he calls “Think Weeks.” While running Microsoft, Gates would take a helicopter or seaplane to a secluded waterfront cottage (a little different from impoverished Joseph Campbell, who kept a one-dollar bill in his top drawer in Woodstock to assure himself he was still okay). Gates would read technical papers from morning to night, often getting through over 100 in a week. Supposedly, in 1995, it was one of these weeks that inspired his seminal paper, “The Internet Tidal Wave,” which led Microsoft to develop its own internet browser. Other breakthroughs in Gates’ thinking came in virtual mapping services and software security.

What does all this have to do with investing? Well, nothing really – but also everything. Because for us, investing is all about coming up with the ideas that don’t come to others. And for the sparks to fly, you need enough base material to work with – the stuff that comes from reading a lot and reading widely – and enough empty space for your mind to make connections. NYU professor Aswath Damodaran, often called the dean of stock valuation, said in a recent interview that our hidden power as humans is our ability to connect unconnected things – and the empty mind is where those “ah-ha” moments happen. His worry is that today we have fewer empty moments, so busy are we being ever more productive and searching for ever more information.

We never know where good ideas will come from. But it strikes us that the combination of deep reading and emptiness is a great place to start. We’ve also always believed that “generalists” can make the best investors. Generalists excel at pattern recognition and connecting the dots across scattered domains. Rather than scrabbling over, say, the very best estimate of a company’s operating earnings, generalists are more likely to seek out informed outsider views and come up with a different perspective.

What did reading for nine hours a day for five years do for Joseph Campbell? We’ll never really know. But we do know that Campbell is the scholar responsible for delineating the archetypal “hero’s journey,” which is so deeply ingrained in our human psyche that it appears over and over again – across traditional sagas and religious myths, modern novels, and even Star Wars. That insight probably would not have come without years of reading Jung, Nietzsche, the Hindu Upanishads, Norse mythology, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, and on and on. It is pattern recognition extraordinaire.