Electronic waste, or “E-waste,” is the byproduct of our ever-increasing appetite for electronics, including smartphones, tablets, laptops/desktop PCs, e-cigarettes, small and large household/kitchen appliances, and flat televisions. We not only own more of these devices than ever before, but have come to view many of them as disposable after a few years of use.

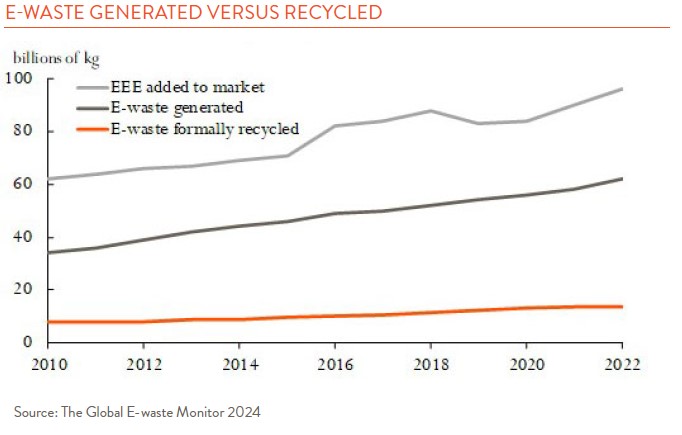

The problem is getting worse. Consumers around the world are generating more E-waste every year, with less than a quarter formally collected and recycled. According to the The Global E-waste Monitor 2024 Report, from 2010 to 2022 the amount of electronic and electrical equipment (EEE) on the market expanded 3.7% annually to 96 billion kilograms while the annual level of E-waste grew faster, at 5.1%. More concerning, recycling rates have not kept pace (see chart below).

The bulk of E-waste is not formally recycled. Around a quarter of it ends up in landfills, while 30% finds its way to the informal recycling industry in lower-income countries. Why does this matter? It’s toxic.

E-waste is composed largely of metals, plastics, and other materials like glass, minerals, and composite materials. The Global E-waste Monitor 2024 report estimates that 58 thousand kilograms of mercury and 45 million kilograms of plastics containing brominated flame retardants are released into the environment annually due to improper disposal or recycling of E-waste. With temperature exchange equipment like refrigerators, freezers, and a/c units, comes the added hazard of releasing refrigerants into the atmosphere, negatively affecting the ozone layer and contributing to climate change. Even without burning or dismantling, the combination of time and warmer weather can result in these toxic materials leaching out of landfills, contaminating the soil and air with harmful chemicals such as lead, cadmium and beryllium. The World Health Organization has warned that exposure to toxic E-waste could lead to adverse health consequences such as negative birth effects, adverse mental impacts on children, and respiratory issues.

Similar to the theme with plastics and other high-income country garbage, E-waste exports often end up in lower income countries with limited environmental regulations. The amount of E-waste transported across borders is difficult to measure accurately as most of it is shipped illegally as used electronics for resale or reuse. Some estimates are that around two-thirds of the used electronics trade is actually E-waste.

While the informal recycling industry can provide jobs, the health and environmental cost can be tremendous. Alexander Clapp, in his latest book Waste Wars, takes us to Agbogbloshie, a slum in Ghana built on a landfill comprised largely of the Western World’s E-waste. Agbogbloshie’s industry is not only about dismantling electronics for parts but also about extracting metals in any way possible. Clapp describes how one of the groups at the bottom of the slum’s economic hierarchy, known as “burner boys,” use fire to extract copper from plastic encased cables. The fires are not fueled by wood or other paper products, but rather leftover plastic from TVs and other electronics, old tires, and even the Styrofoam liners from refrigerators. The resulting conflagration frees the copper from its encasement but also causes great harm. He reports that chicken eggs from the area are “probably the most poisonous on Earth” and that the surrounding slums are “full of hands missing fingers, feet shorn of toes, limbs pocked with burns, and the occasional one-eyed dismantler.”

The cruel irony of the copper recycling process is that its most likely use will be as another piece of electronic equipment that could end up back in Agbogbloshie.