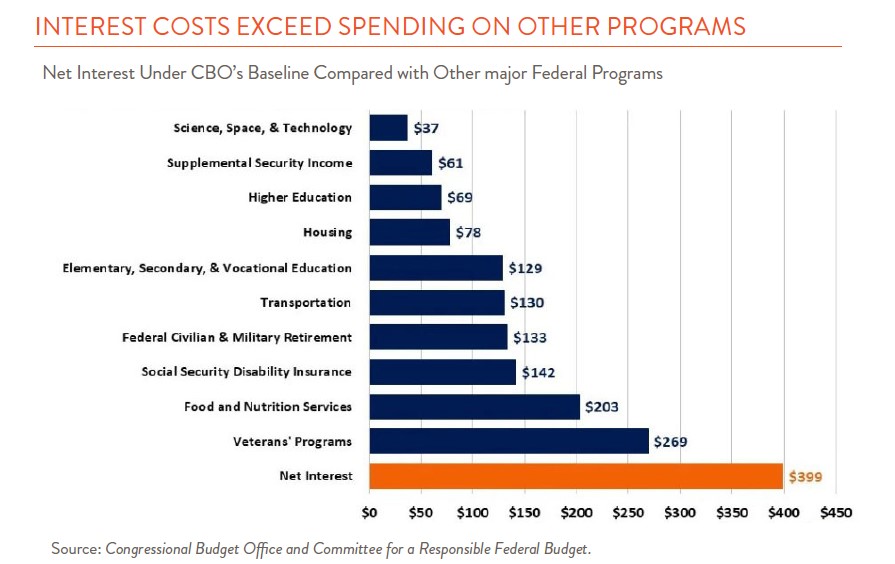

Earlier this month, the Treasury Department reported that the nation’s gross debt for the first time exceeded $31 trillion. Interest on these obligations is expected to be approximately $400 billion this year or about 8% of all federal revenues collected. The debt’s relatively short maturity profile means that interest rate increases will start pressuring federal finances soon. Even today, the federal government’s interest tab well exceeds what is spent on many important federal programs (see chart below.) Further increases will undoubtedly foster heated debate over funding priorities and debt levels.

For any borrower, including the U.S., the capacity to carry debt is a function of three things: the level of debt incurred, the income available to support that debt, and the interest rate applied. Let’s consider the future path of each of these separately.

Record levels of federal debt are hardly something new. Except for a few brief periods (after WWII and the late 1990s), the nation’s outstanding debt has grown steadily. That history together with structural forces at work today such as an ageing population, rising defense spending, and higher energy costs, suggest higher, not lower, levels of debt are more likely going forward.

As is the case for individuals, any assessment of debt capacity should include not just the dollar amount outstanding but the ability to carry that debt. For an individual, for example, credit card limits are set after considering income. For a nation, debt burdens are considered relative to gross domestic product or GDP. While annual GDP growth rates of 3%+ were possible in the past, a 1%-2% rate is more likely going forward given our now more anemic workforce and productivity growth. For individuals, lenders have some clear rules about how much debt is “too” much. For countries, and the U.S. in particular, answering this question is more complicated. The U.S. government’s position as the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, gives it more leeway to print dollars to service debt. But investor’s confidence in our creditworthiness should not be considered unlimited. The U.K. just learned this difficult lesson when it had to step back from its recent decision to cut taxes — a potentially inflationary and credit- negative move.

Finally, what about interest rates? For most of the last 30 years, ever declining rates made taking on more debt a relatively painless affair. Now, that calculus has changed. Higher rates will pressure federal finances in the near term; the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget recently calculated that a 1% increase in rates would boost interest costs by approximately $38 billion. But I would be careful not to extrapolate these costs too far into the future. The Federal Reserve is determined to fight inflation at any cost. Their efforts will likely depress economic growth and may eventually, lead to lower interest rates.

A snapshot of federal finances today does not paint a rosy picture. The chances of any successful effort to bring federal spending under control appear low. The economic growth needed to support higher debt levels seems out of reach, and interest rates are going up – at least in the short term. But there is one overlooked positive today. The outstanding debt now owed is a fixed dollar amount. Thanks to inflation, however, the amount of income or GDP available to support that debt is rising. This dynamic causes our debt-to-GDP level, an important measure of debt carrying capacity, to drop.

High inflation rates contributed to the sharp decline in public debt after WWII. Conditions are quite different today, but these same forces could give us a little breathing room in the near term. Longer term, no borrower, the U.S. included, can keep growing its debt faster than its income. Low interest rates helped us ignore this economic reality for many years. Higher interest rates are now bringing it back into focus.