CNBC recently reported that 72% of recent homebuyers feel regret about their purchase — either because they paid too much or because they rushed the process and made too many concessions. Whether that survey is robust or accurately reflects reality, I don’t know. But I certainly can believe there is regret out there — because there always is. The threat of regret is ever present, lurking behind every decision we make.

Nobel-Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman has written that, “Regret is an emotion, and it is also a punishment that we administer to ourselves” (Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011). It is profoundly painful because it shines a spotlight on our own agency in poor outcomes. And it is most intense “when you can most easily imagine yourself doing something other than what you did.”

Because regret is so painful, we start anticipating it as soon as we know a decision is at hand – and our desire to avoid it sometimes leads to suboptimal decisions. One famous (and humorous) acknowledgement of this comes from Harry Markowitz, who won the Nobel Prize for working out the complex mathematics behind the tradeoffs between investment risk and return. Markowitz is the father of Modern Portfolio Theory and a finance superhero, but when Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal asked him if he used his own work for his personal investment portfolio, he said no:

“Instead, I visualized my grief if the stock market went way up and I wasn’t in it – or if it went way down and I was completely in it. My intention was to minimize my regret . . . So I split my contributions 50/50 between bonds and equities.” (This is from a classic 2009 article titled “Investing Experts Urge, Do as I Say, Not as I Do.”)

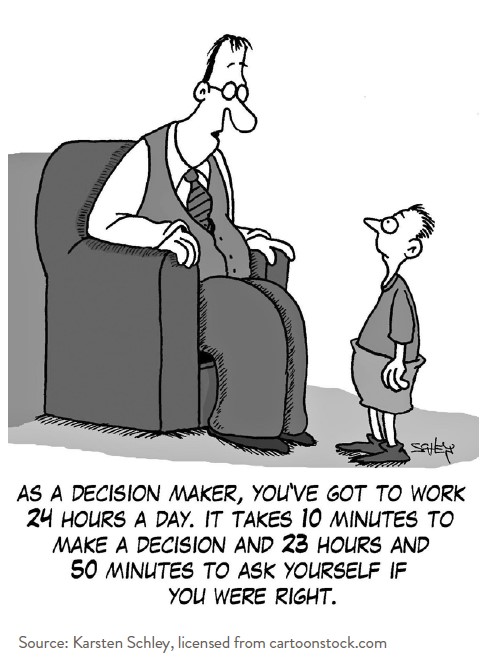

If Nobel Prize winners struggle with regret, what are we mere mortals to do? On the one hand, it makes sense to limit our regret exposure because regret makes us do silly things (reverse course at the wrong time, buy too high, or hide our heads in the sand.) On the other hand, focusing too much on regret isn’t good either. If we worried less about kicking ourselves every day for the next year, we likely would take a much longer view on our portfolios. We would tilt our portfolios toward cheaper “value” stocks — and probably, we would buy more international assets as well.

Ultimately, there’s a tradeoff between return maximization and regret minimization, and acknowledging that means it’s important to have what Kahneman calls a “well-calibrated sense of your future regret.” That is, if you’re prone to regret, Kahneman advises limiting your regret exposure. But if you’re less prone to it, move the dial toward long-term return.

Remember, whatever choices you make – whether you go conservative or aggressive, active or passive, ESG or not – there’s always going to be a portfolio out there that looks better than yours at any given moment. This doesn’t mean you’ve failed as an investor. But unless you’re superhuman, you’re going to feel jealousy and regret, and you’ve got to prepare for that.

One thing to try is to slow down, project yourself into the future, and imagine how badly you will feel if you’re totally wrong about a decision. It sounds simple, but few people really think about the possibility of being dead wrong. And it matters. Today, we’re in a time fraught with big questions: Are we in a sustained bear market or is the worst over? Will inflation kill us, or recession? Or both, or neither? How do we decide if we should be dialing down risk or seeking out opportunity? Investor Howard Marks advises: “Try to travel into the future and look back . . . What you think you might say a few years down the road can help you figure out what you should do today.”

And one final note: Watch out for emotional extremes because those are what get us most often. Howard Marks says that “…in the real world, things generally fluctuate between ‘pretty good’ and ‘not so hot.’ But in the world of investing, perception often swings from ‘flawless’ to ‘hopeless’.” I always try to remember those words because it’s a slippery slope to thinking, “If I don’t get in (or out) now, I never will!” And, that is exactly the thinking that makes us pay too high a price or pull out all the stops in a competitive bidding process – and then feel regret after we’ve won.