Last month we wrote about how unaffordable housing has become as the sharp rise in home prices and interest rates have outpaced income growth. But that was for those buying a home – what about for renters who don’t have to take out a mortgage?

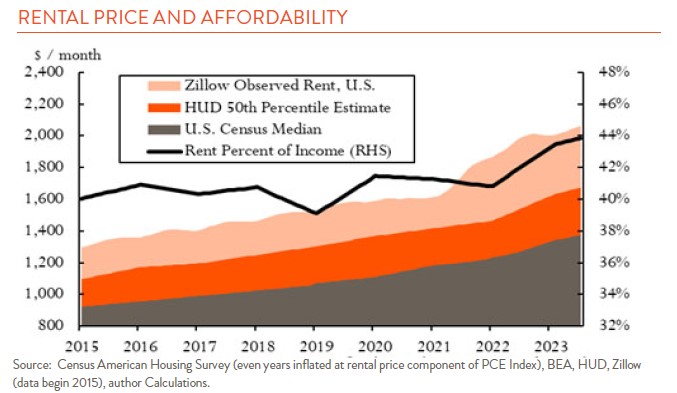

Renters have not experienced quite as dramatic a decline in housing affordability as buyers, but it’s gone from bad to worse. The chart on the right shows country-wide median monthly rental figures from Zillow, the Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD), and the Census. These things are hard to measure, and they show materially different median rent ($1,375 to $2,050 for 2023), but they all show an acceleration in prices in 2021-2023.

Comparing the HUD rent figure to renter household income, monthly payments accounted for around 40% of income until 2022 when they started rising to today’s 44%. Keep in mind, the affordability threshold is 30% of income, so renting in the U.S. hasn’t been affordable for a while. A lot of that has to do with renter household income being well below homeowner household income, with the Census estimate at 52-54%.

But we might have thought renters would be insulated from the dramatic housing price and mortgage swings given they don’t buy and they don’t borrow. So why has rental affordability deteriorated as well?

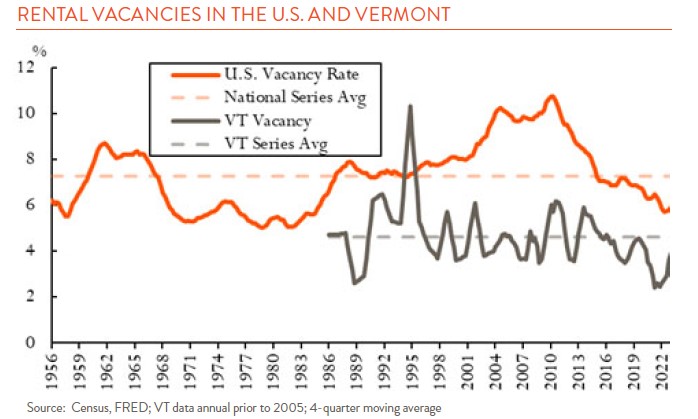

Perhaps the most obvious answer is that owners pass on increasing costs to their tenants. As monthly housing payments have increased as well as the cost of services associated with owning a home, owners need to charge more to keep up. Another factor is a familiar one from last month: lack of inventory. According to the Census, in 2022 rental vacancy rates reached 5.6%, the lowest level since 1984. While it has ticked up recently, it’s still below the long-run average for the Census’s data (chart at bottom).

Additionally, interest rates still play a role for renters. A typical housing progression is to rent until you buy your first home. Those first-time homebuyers are the ones most impacted by affordability because they generally need to take out larger (loan-to-value) mortgages. Facing the rising all-in cost of buying a home, renters have stayed put, keeping rental units off the market.

There’s also a demand factor. The pandemic led to different patterns of household formation. Many of those who had moved in or remained with relatives or friends entered the search for housing all at once, releasing a flood of demand.

Closer to home, Vermont’s Housing Finance Agency notes the problem is particularly acute in Vermont. They point to Census data which showed Vermont had lowest rental vacancy rate in the country in 2022 (it’s since moved to 8th lowest). At the same time there has been more demand to live here, with population growth at -0.01% annualized for the ten years prior to the pandemic and at +1.22% since.