You have saved diligently for 20, 30, even 40 years. Now comes the big question: How much can you comfortably withdraw from your nest egg and not run out of funds by the time you die? This is not an inconsequential question since life expectancy is up significantly the past 50 years. The average 65-year-old U.S. male is expected to live another 18 years. Back in 1970 it was only 13 years. The average 65-year-old U.S. female can, knock on wood, live another 21 years, up from 17 years 50 years ago. We must support ourselves for almost a quarter of our lives with what we have saved, Social Security, and any fixed pensions we might be lucky enough to have. That is a lot of time and a lot of money required.

So, what about this 4% rule? The idea is that a portfolio of financial assets should be able to produce a return great enough to allow you to withdraw 4% each year and still have your nest egg grow by an inflation factor of 2% to 3%. This has been the case in the past. Over the past 10 years, a good time for Wall Street, stocks have had an average annual return of 17% and bonds 4%. Looking at a longer time frame, say the past 20 years, which includes the difficult decade of 2000-2010, stocks still averaged 9.5% per year and bonds 6.5%.

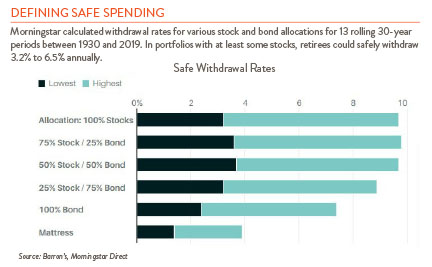

Morningstar crunched the numbers for 30-year periods from 1930 to 1990 and found investors could withdraw between 3.2% and 6.5% and have a 90% chance of not running through their savings with a portfolio invested in at least some stocks.

But what about the future? Morningstar is less optimistic. They see lower investment returns going forward and think a withdrawal rate at the lower end of the range (3.2%) is more appropriate if your investments are split evenly between stocks and bonds.

Our thinking is 4% is still a good place to start, but the key is to stay flexible. We are not trying to predict future returns — just saying, start at 4%, and if investment returns pull back then cut back your withdrawals as much as feasible. When investment returns advance again, increase the withdrawal rate. Colleges typically take the average size of their endowment over a three to five year period and then apply their withdrawal rate. This smooths the ups and the downs of the market. The 4% rule is not cast in concrete, but it has been a reliable guide. Do not give up on it just yet, but stay vigilant and flexible.