Over the last two years, six out of 10 of the world’s largest food companies have set goals to increase regenerative agriculture in their supply chains. Regenerative agriculture refers to practices aimed at replenishing topsoil levels, improving soil health, and sequestering carbon. Examples include planting cover crops to reduce soil erosion and fertilizer use, mixing companion crops with cash crops to increase microbial diversity and beneficial insects, and grazing livestock on fields to trample organic matter into the soil and deposit manure.

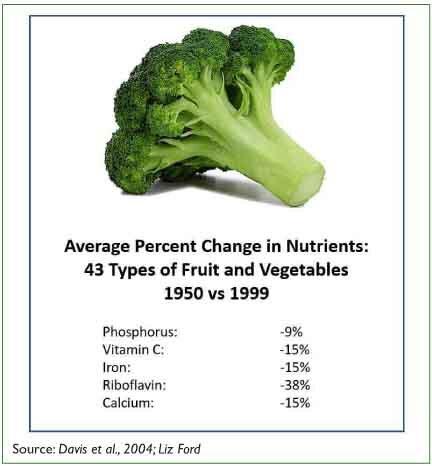

The focus for many food companies is to become more regenerative in order to reduce carbon emissions. Public scrutiny is on the rise as the United Nations estimates that nearly a quarter of carbon emissions come from agriculture and forestry. Emissions are only one part of a larger problem, though. According to researchers at Cornell, the topsoil that supplies our food is eroding 10 times faster than it can be replenished. Additionally, a growing body of research is finding that the food industry’s focus on fast growth and high yield is depleting the nutritional value of our crops.

There is evidence to support that organic farming – which doesn’t use synthetic fertilizers, herbicides or insecticides and often relies on regenerative techniques – can have less environmental impact while producing more nutritious food. So, it’s encouraging to see companies like General Mills and Danone approach the soil challenge by helping some farmers in their supply chains transition to USDA Certified Organic.

The process to become an organic grower can be costly and risky for farmers, even though the transition can potentially increase profitability in the long run. The certification process takes three years of demonstrated organic practices before a farm can sell to the organic market, combined with investments in equipment and education. It also takes more workers to farm organically, as weeding and harvesting may need to be done by hand. The good news is that the demand for crops is high and there is considerable white space for suppliers. Organic food sales in the U.S. have more than doubled in the last 10 years, but according to The Washington Post, only one percent of our farmland is certified organic and we still import the majority of our organic food.

The labor intensity of organic farming can make it less feasible for large industrial farms to transition, opening up opportunities for smaller growers. However, years of consolidation and price wars in the food industry have weakened the supporting systems for small farms. Overall, small farms have less access to financial, wholesale, and retail markets. Corporate partnership may provide a bridge to organic certification and access to a reliable buyer. On the other hand, there are some potentially disruptive enterprises on the horizon that aim to build and support alternative markets and autonomy for organic producers.

Iroquois Valley is the first organic farmland real estate investment trust (REIT) in the U.S. The company focuses on providing financing for organic farms and those looking to transition to organic farming. A number of start-ups, like CropSwap and WhatsGood, enable organic farmers to market and sell directly to retail and wholesale customers. To protect the premium value of organic produce and hold food companies accountable, Farmer Connect and other software developers are leveraging Blockchain to verify that ingredients come from legitimate organic sources.

Small organic growers are also building networks with each other. One national initiative, The Farm Generations Cooperative, seeks “to expand the market share and viability of small farmers with fair, farmer-owned technology.” These alliances could increase financial benefits if the science surrounding agricultural carbon capture pans out; without a coalition, small farms may struggle to compete in the nascent market to sell carbon offsets.

Ultimately, the need to increase food sustainability will likely provide investment opportunities in companies throughout the system, from seed to plate. Seeking out those companies that partner with and support organic growers could benefit us all by keeping decisions critical to our food supply close to the ground.