Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is becoming widespread, and education is already feeling its impact. The technology will, without a doubt, have broad implications for how we acquire learning and educate our children and the workforce.

First, the good: AI can be a huge boon to efficiency. A 2022 survey conducted by Merrimack College found that teachers spend half their time on non-teaching tasks like grading, planning, communicating with parents, professional development, and school committee work. Commonly used GenAI tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini can help create lesson plans, practice problems, and classroom activities in minutes, and it is easy to imagine other potential benefits.

Squirrel Ai, for example, creates personalized, data-driven lesson plans by combining teacher-designed curricula with AI algorithms—hopefully providing a more engaging and effective learning experience. Magic School allows students to have simulated conversations with historical figures, and MATHia focuses on providing each student with a personalized one-on-one coach. These tools already serve millions of students.

But there is also a dark side. Cheating—and how it damages learning—remains a big concern. Students use AI to draft essays, prepare book reports, and solve math problems. Cheating has always existed, but AI has changed the game and made it more difficult for educators to ensure that students are actually learning. While software like Turnitin, which assesses if text has been written by GenAI, is useful, it may not be a long-term solution. Teachers also have raised valid concerns that surveillance-based AI monitoring systems can contribute to distrust between teachers and students and strain relationships.

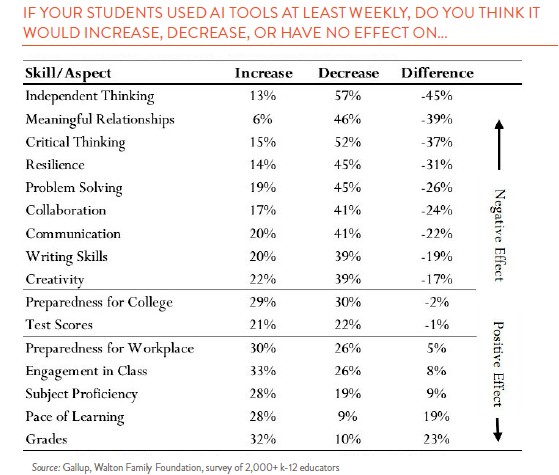

And the problem might just be AI tools in general. A recent study from Gallup surveyed K-12 teachers and found negative views about the impact AI has on a host of student skills, including independent and critical thinking, creativity, writing, and problem solving (see table below). To highlight one particularly dismal outlook, 46% of teachers believe AI tools will decrease students’ ability to build meaningful relationships, with just 6% believing AI will help—not good in a society already struggling with social isolation. AI was generally regarded as having a positive effect on grades and the pace of learning, and neutral on college prep and test scores.

Whatever its impact, as GenAI becomes more a part of our lives, the focus may need to be less on policing its use and more on understanding and embracing its ability to improve how we learn and become productive in our careers and society. Communication will be key. MIT Sloan School of Management has offered some suggestions, including setting clear policies and expectations, defining plagiarism and cheating within the context of GenAI, promoting transparency and dialogue, fostering intrinsic motivation, and ensuring inclusive teaching. While those suggestions are helpful, schools have found designing and adopting AI policies difficult and many still lack clear guidance. Much work remains to be done.

Despite all of this, the use of AI in education will surely continue to expand. OpenAI and Microsoft just announced a $23 million investment in AI training for teachers, and a recent executive order promotes “Advancing Artificial Intelligence Education For American Youth” with over 60 organizations pledging support. We cannot discount the possibility that effective teaching of GenAI tools will prove important in positioning students for future success in the workplace. But the balance between genuine comprehension and knowledge aided by AI versus total reliance on AI will be important to get right.