For most of the past 15 years, the U.S. has suffered from a productivity problem. Except for a spike after the 2009 Financial Crisis, productivity gains have been stuck at 1% per year over the past decade, or half the long-term average. Why does this matter? Economies that produce more with the same number of workers grow faster, and that faster growth supports higher wages.

Theories of the cause of this poor performance have varied. Some economists have suggested that we are simply not measuring productivity correctly. How, they claim, do you account for improvements imparted by services like Google Maps or Waze? Others suggest that we have simply become less innovative and that the advances of today (consider streaming services) compare poorly to the productivity enhancing leaps of yesterday like electricity and the internal combustion engine. Whatever the answer, the good news is that recent data shows a significant improvement in our nation’s results with first quarter productivity rising at a 5.4% annual rate – a full 4.1% above year-earlier levels.

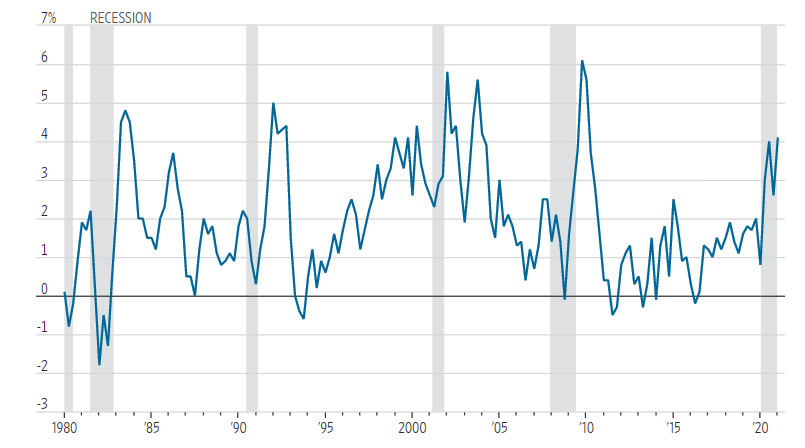

As the chart below shows, it is not unusual for economies to experience rising productivity coming out of a recession. The reason here is intuitive; early in a recovery employment gains tend to lag the actual pick-up in demand as businesses make sure the turnaround is real and hire and train new workers. That certainly appears to be the case today.

NONFARM BUSINESS PRODUCTIVITY

Change from quarter one year earlier:

Sources: The Wall Street Journal; Labor Department via St. Louis Fed

There are several reasons, however, that suggest the most recent productivity gains may be more sustained in nature. First, the pandemic forced many businesses to figure out how to produce more with fewer workers (think telehealth and electronic menus). Some of these “innovations” will fade but many will continue to spread across the economy.

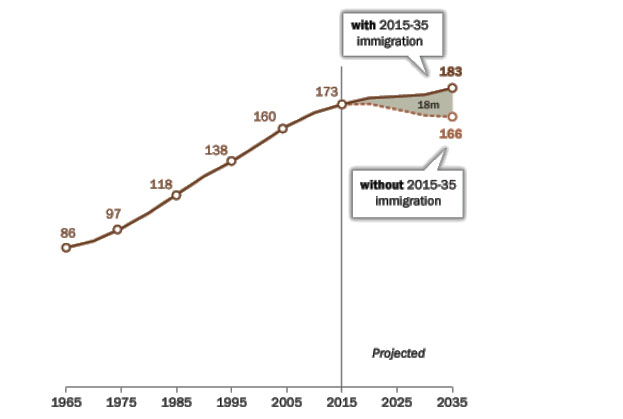

Second, the unprecedented level of fiscal and monetary stimulus together with the nation’s slow-growing work force could mean that businesses continue to have trouble hiring to keep up with demand. In a recent study, the Pew Research Center projected that the total growth of the labor force over the next 20 years will be lower than the total growth in any single decade since 1960. Many businesses, faced with a shortage of workers and related rising wages, will turn to productivity enhancing technology and process related improvements to control costs.

WITHOUT FUTURE IMMIGRANTS, WORKING-AGE POPULATION IN U.S. WOULD DECREASE BY 2035

Working-age population (25-64), in millions

Note: Numbers for 2015 onward are projections. Source: Pew Research Center estimates for 1965 – 2015 based on adjusted census data; Pew Research Center projections for 2015-2035.

Finally, consider the shifting global economic landscape. For most of the past 50 years, the U.S. played a leading role in the global economy. Investments in everything from the federal highway system to technology and healthcare helped it sustain this lead. But the tremendous economic advances in countries such as China together with lagging investments here at home mean that the U.S. can no longer live off its past successes to stay on top. The current administration’s effort to bolster key industries such as semiconductor manufacturing suggests a shift toward more focused industrial policies aimed at retaining our economic sovereignty. Whether this approach proves successful over time remains to be seen. In the meantime, investments into key sectors of the economy and basic R&D may well translate into productivity improvements going forward.