Are we collectively reading more than we used to, or less? Most would probably guess less, and so would I, which is why I was surprised to read in one of Kevin Kelly’s books that “The amount of time people spend reading has almost tripled since 1980.”

I haven’t found anything to back up Kevin Kelly’s claim, and he wrote this in 2016, which may seem like an age ago in tech years (The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces that will Shape our Future). But it’s worth a thought.

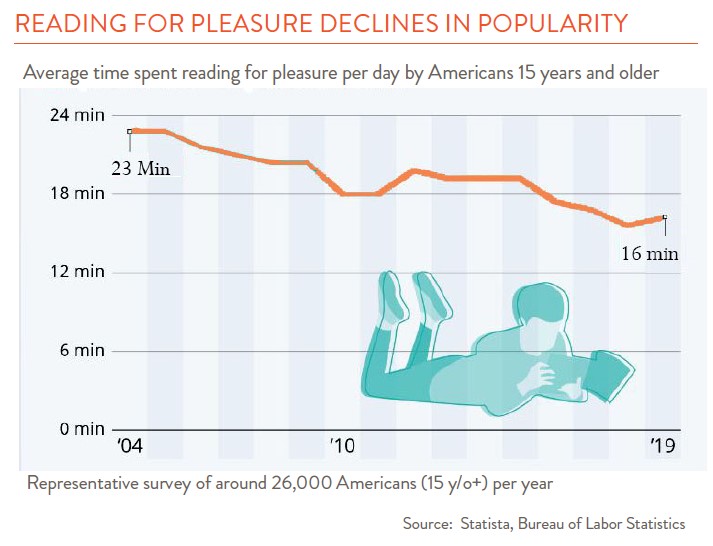

Most studies have found we spend much less time reading for pleasure than we used to, at least relative to the early 2000s, as the chart here shows. But much remains unclear. For one thing, this data was gathered via surveys, and we know respondents are notoriously unreliable when asked about their habits – they are not very good at recalling things, and they often try to make themselves look better. More important, what counts as “reading for pleasure” anyway? Books? Magazines? Blogs and Substacks? Your newsfeed on social media? Where do we draw the line?

When Kevin Kelly says we’re reading more than ever, he’s talking about everything — all the words in print, on paper, and on all the monitors and screens around us, whether in our pockets or plastered to ever more surfaces. And he really means everything: “. . . we now read words floating nonlinearly in the lyrics of a music video or scrolling up in the closing credits of a movie. We might read dialog balloons spoken by an avatar in a virtual reality, or click through the labels of objects in a video game . . .”

For context, Kelly is co-founder of the magazine Wired and a techno-optimist (if you’re curious, read Noah Smith’s interview with him from 3/7/2023).

Kelly also says we are writing more than ever too. At the time he published The Inevitable, more than 60 trillion web pages had been added to the World Wide Web, and ordinary citizens were writing 80 million blog posts a day. “If we count the creation of all words on all screens,”

Kelly wrote, “you are writing far more per week than your grandmother, no matter where you live.”

The interesting question is what all these words in new formats are doing to us. Most everyone believes we bring a focused mindset to printed books but a casual one to online materials – and it’s known that we retain less when reading online content. Books are fixed, fully formed, and meant to be read in linear fashion from front to back. Digital materials are changing, floating bits that encourage flickering glimpses as the eye wanders and jumps.

The medium makes a difference. Think about how a large foldable newspaper page encourages us to scan the columns. Or take the opposite, a small screen showing one word at a time. Imagine burying yourself in a novel where you see just one word at a time rather than one page. Amazon’s Word Runner (pictured) tried doing just that, though the concept never took off.

We almost certainly are reading fewer books today than we once did. But perhaps books are no longer the relevant unit of measure. Ever since Gutenberg invented movable-type printing, books have been our cornerstone of written content. They have been a complete set of pages bound between two covers. But as books have migrated to digital formats, they’ve started morphing into something else. Now they hyperlink to other texts or allow readers to share highlighted passages, which makes reading social. As we tag, cross-index, and hyperlink more passages in more books, perhaps we will think of books less as discrete objects and more as components of a universe where we jump among wiki-style linked pages across books. Perhaps in the future, readers will buy not just whole books, but also single chapters, or collections of pages or passages. The possibilities are wide open.