The latest job statistics held mixed results. The good news? Another 315,000 jobs were added to the economy, bringing the total number of people employed to just shy of the 158.87 million peak logged back in February 2020. But while the closely watched labor force participation rate inched ahead to 62.4%, it still lies below prepandemic levels.

Policy makers have spent a lot of time trying to understand why the labor market has taken so long to recover. Most point to several recent trends including the lingering health effects of Covid, and the available (though diminishing) pool of stimulus funds which allowed many to step back from work. Lower immigration levels, the result of the pandemic and more restrictive policies, have also contributed to our workforce shortages. Finally, there is the concept of the Great Resignation, a term first coined by Organizational Psychologist Anthony Klotz back in May 2021. Klotz predicted then that the pandemic and related shift to work-from-home policies would cause employees to exit the workforce after reconsidering their work conditions and career goals.

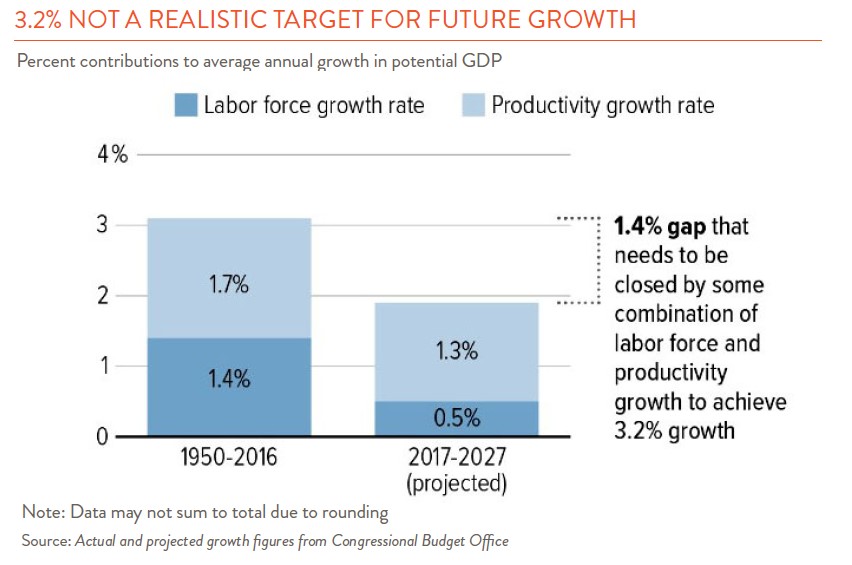

While these trends will likely revert to normal levels over time, there is a more significant and long-lasting factor impacting our nation’s workforce today. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that over the next decade, the civilian labor force is expected to grow at an average annual rate of just 0.5%. This anemic rate, which is half of the previous decade’s level, is the result of low population growth and baby boomer retirements. Only two forces – labor force growth and productivity growth – drive increases in the economy. While gains in productivity, achieved by better technological innovation or processes, could help offset our labor force deficiencies, the prognosis here is not encouraging (see chart below).

The labor force problem is not unique to us. Developed economies around the globe have been struggling for years with the implications of these same demographic trends. Consider that according to market research firm Statista, Japan’s labor force has grown just 1.2% over the last 25 years while China’s work force is down 2.1% from its 2015 peak.

Every country is managing the challenge in a different way. Some, like Russia, have offered financial incentives such as lower taxes or cash rewards to boost fertility rates while others have eased immigration rules. Most of these measures have done little to change the powerful demographic forces at work.

This past Spring, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida tried a different tack. After years of unsuccessfully trying to boost population and economic growth, he announced a plan to shift the country’s focus toward “a new form of capitalism.” In his original comments, he outlined plans to shift the nation’s policy focus away from outright growth and toward plans aimed at reducing social disparities. These efforts would include significant investment in human capital, innovation, and digitization. While the general strategy was well received, several of the more disruptive ideas were dialed back after investors raised concerns that they would hurt shareholder profits.

The U.S., I suspect, would also experience resistance to similar policies. The idea that faster growth leads to rising living standards (an implicit promise to most citizens) is a central tenent of our capitalist system. Recent political discord and economic indicators have raised serious questions about our ability to deliver on this promise with current policies. But it is not at all clear that slower growth will make the task any easier. How we balance the growth that we can achieve given our demographic circumstances with other priorities such as income equality and biodiversity will be a defining issue of the years ahead.