The pandemic profoundly changed U.S. labor markets. Between March and April of 2020, a total of 20.5 million people left their jobs – the largest one-month drop since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began its employment survey in 1939. The labor market has since recovered. The unemployment rate today stands near a record low of 3.8%, and the workforce participation rate of 62.8% is nearing prepandemic levels. Whether the U.S. job market can sustain this strength remains the open question today. Here are a few things to consider.

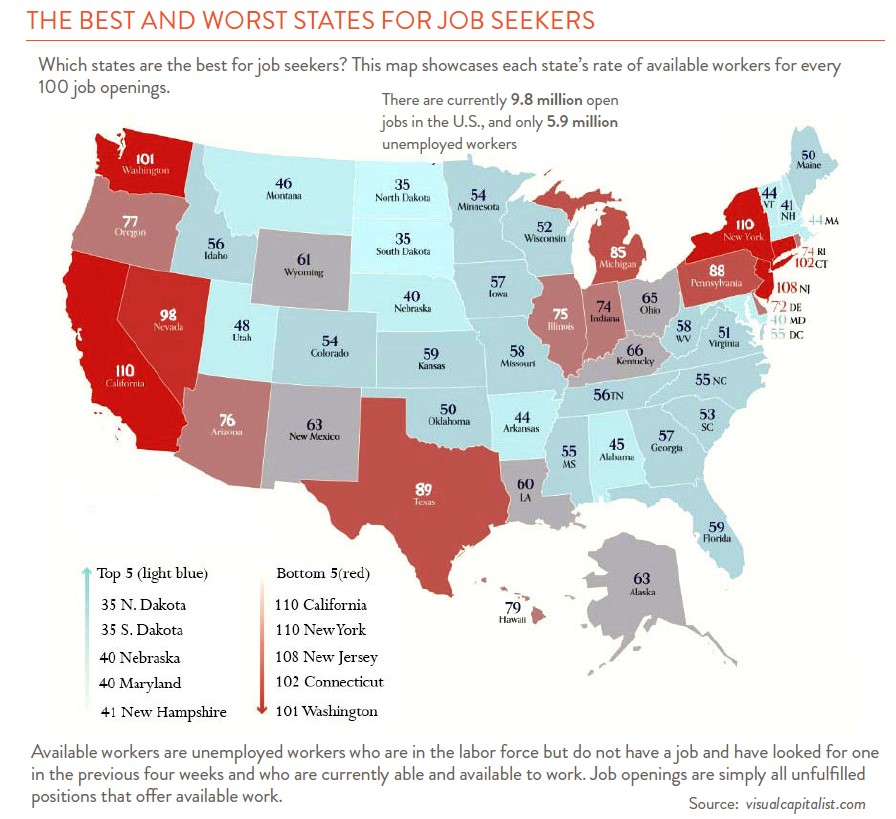

Not one but many markets: While we tend to focus on national labor statistics, it is important to remember that large differences exist across geographies and industries. Take a look at the chart below. Back in July there were 75 workers for every 100 jobs open in the U.S., but trying to find a job in California was much tougher than in St. Louis. Similarly, employment prospects in the chronically understaffed healthcare field remain much rosier than in leisure and hospitality. Perhaps more than ever, finding a job today depends on what job you are looking for and where.

Technology matters: Technological innovation has long impacted the nature of work. Sometimes the impact is slow- moving – consider how the introduction of new industrial processes in the early 1900s led to steady, decade-long declines in manufacturing jobs. Sometimes the impact is swift, as was the case when improvements in broadband capacity and teleconferencing software allowed record numbers of employees to work from home in the early days of the pandemic. Today, the big question relates to how artificial intelligence (AI) will change the nature of work. While new technologies often lead to improved working conditions or productivity levels, they can also cause painful market “dislocations” and, in some cases, negative unintended consequences.

It’s all about supply and demand: While it has its own unique characteristics, the market for labor operates much like the market for any other good or service. A shortage of supply (workers) will lead to rising prices (wages) until balance is achieved. This dynamic has been evident as worker shortages caused annual wage growth to spike to almost 5% in 2023 from the 1%-3% rate witnessed before the pandemic. The recent increase in labor actions is another example of how power has shifted away from business to labor. In 2022, a total of 2,520 union representation petitions were filed with the National Labor Relations Board, an almost 60% increase from year earlier levels. This past summer saw a particular spike with over 1,200 applications filed on a year-to-date basis. Finally, consider the ongoing tug-of-war between managers and workers over work from home policies. At the peak of the pandemic, an estimated 35% of employees worked remotely. While many businesses are pressuring employees back to the office, a full 28.2% work under some form of hybrid model today.

Evolving supply and demand dynamics will determine whether labor’s newfound power advantage persists. Until now, the labor market has remained remarkably resilient with employment levels continuing to gain ground in the face of rising interest rates, elevated inflation, and waning consumer confidence. But some signs of a slowdown are starting to emerge, with job openings, temporary hiring, and the number of workers quitting all down from beginning of the year levels. While a cooling labor market is exactly what the Fed’s policies are designed to achieve in its effort to fight inflation, let’s hope they don’t get too much of what they are asking for.