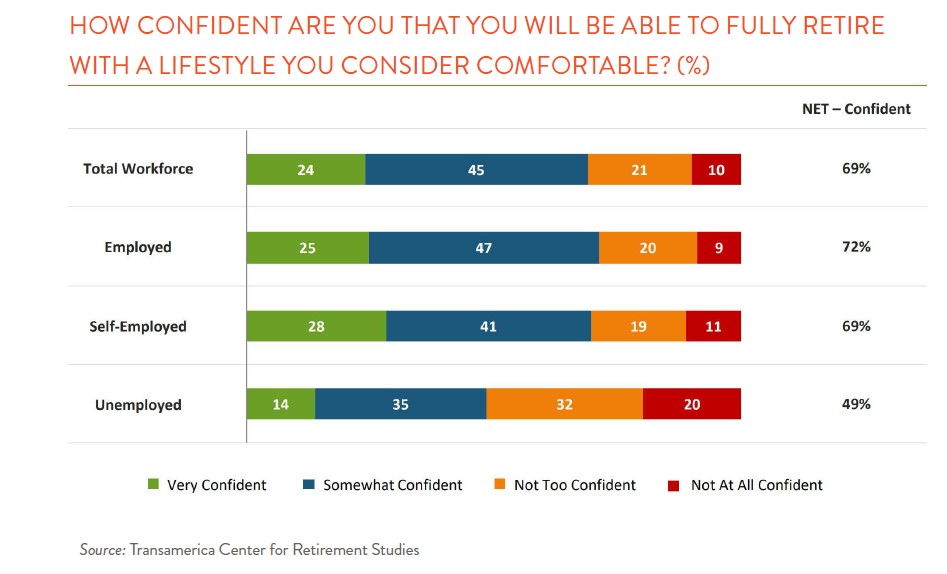

According to a recent survey by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies, 69% of Americans said they were confident about being able to retire comfortably. While that doesn’t seem like a half-bad number, the other side of the coin is that 31% are worried – some deeply so — that they won’t be able to retire well or at all. In the same survey, nearly 40% of respondents said they felt they hadn’t saved enough, and 23% fully expected Social Security to be their primary source of retirement income.

None of these numbers are good, and there are scores of other surveys with more discouraging results. The Federal Reserve’s 2021 report on the “Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households” said a quarter of non-retired adults had no retirement savings at all. And investment firm Natixis found in 2021 that 36% of Americans felt they never would have enough money to retire. It ranked the U.S. 17th out of 44 countries in its global index of overall retirement well-being, while the top five countries were Iceland, Switzerland, Norway, Ireland, and the Netherlands.

So how did we get here? The simple answer is that saving money for a distant future is hard, and leaving it up to individuals means it often won’t happen. Most people prepare for retirement through 401ks or other employer-sponsored plans, but a 2019 study (Biggs/Munnell/Chen) found that plan balances were less than a third of their potential if participants had contributed regularly from age 30. The main reasons for this tremendous shortfall were the immaturity of the 401k system and inconsistency in employee contributions. The 401k didn’t exist before 1978 and wasn’t intended to be the primary vehicle for retirement saving — which means many workers now in their 60s didn’t have access to plans early in their careers. Coverage was far from universal, and participation and deferrals have been inconsistent. In addition, two other reasons for saving shortfalls have been “leakage” through participants taking out loans or tapping balances too early, and high fees.

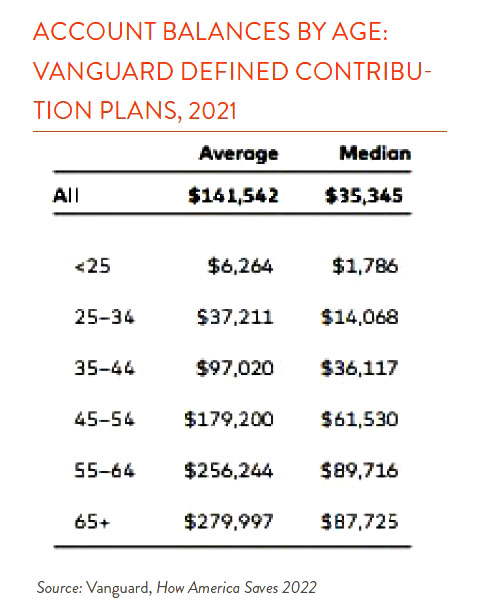

Not all the news is bad, however. Vanguard yearly publishes a report on retirement saving trends, and the most recent, How America Saves 2022, strikes an upbeat tone on the 5 million retirement plan participants across Vanguard’s business. Plan participation and deferral rates both have moved up the last decade, and so have plan balances. That means we’re learning how to make this work. Automatic enrollment — where employees are defaulted into a balanced investment strategy — has been a powerful tool for raising participation. In addition, the increased use of target-date funds, where fund selections are dictated by one’s age, mean that more participants are invested at reasonable rather than extreme asset allocations.

Nevertheless, the Vanguard report reveals that individuals still find ways to sabotage themselves. Nearly a third of Vanguard plan participants did not contribute enough to get their full employer match, which means they left good, easy money on the table. In addition, while excessive trading in and out of assets has stayed reasonably low, the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 spurred a spike in trading activity that likely was wealth-destructive (those who got out of the market likely found it difficult to get back in). Both these behaviors suggest that we have some ways to go on retirement plan design and education. Since we know saving is hard, the more we can get people on autopilot, the better.