In a recent issue, The Economist predicted that by the mid-2030s, solar cells will represent the single greatest source of energy for electrical generation globally. To get a sense of just how big a claim this is, consider that today coal, at 36%, is the largest source and solar stands at just 6%. While the shift away from coal toward solar has been going on for years, the rate of change has accelerated and been consistently underestimated. What is driving this growth?

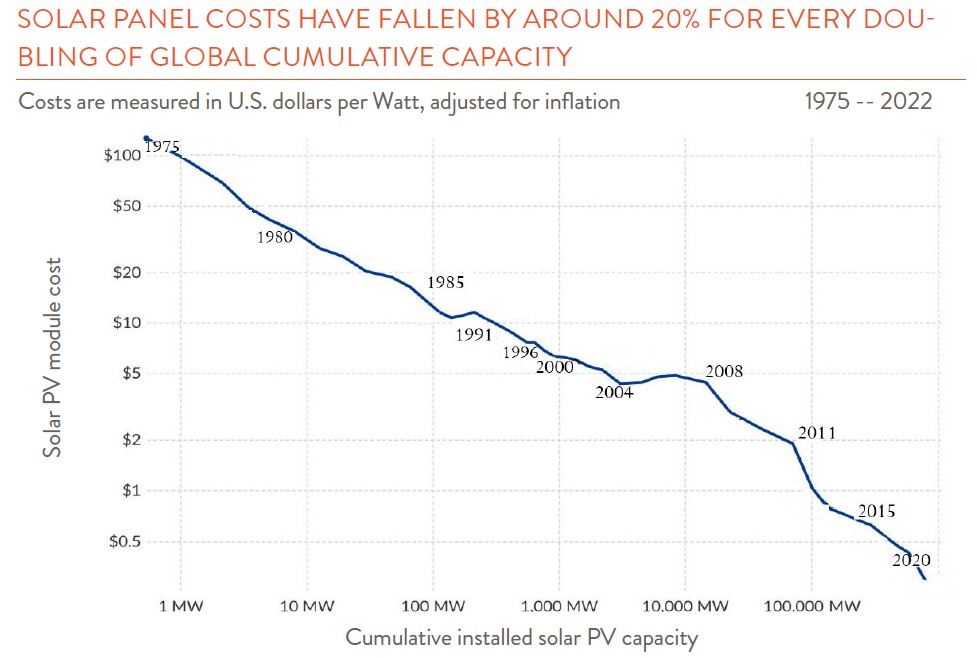

To improve energy security and reduce carbon emissions, governments around the globe have implemented policies to foster solar production and adoption. Most notably, China has poured billions into its domestic industry through a broad range of subsidies and tax incentives. The result of this investment has been impressive. Wood Mackenzie, an industry consulting firm, reports that last year China’s solar module production capacity reached 1,000 GW, almost five times that of the rest of the world. As is true with a range of other manufacturing industries (think cell phones or EV batteries), competitors will have a hard time displacing the now entrenched Chinese firms. China’s well-established solar manufacturing ecosystem provides an edge on things like quality control while its sheer scale of production translates into lower unit costs. The above factors have created something of a “flywheel” effect too where falling costs spur additional demand which leads to increased production which lowers costs further (see chart above).

The solar industry has had a range of attributes that most investors would consider attractive; a growing, global demand profile, supportive government policies and falling unit costs. But despite this, the industry has been a terrible place to put your money over much of its history. Consider that Invesco’s Solar ETF (TAN), a fund composed of leading global solar firms, has produced a -9.0% average annual return since its inception back in 2008. In the early years of solar’s adoption, ever changing consumer subsidies created something of a boom-and-bust cycle both in the U.S. and Europe. More recently, China’s massive investment in expanding its solar supply capacity, estimated at over $50 billion since 2011 alone, has driven many European and U.S. competitors out of business. While this investment has driven solar unit costs down, it has also left the global market oversupplied. Most western manufacturers that remain in business depend on government incentives to survive, a condition that is not likely to change anytime soon.

According to recent IEA data, installed solar capacity is now doubling every three years. What, if anything, might slow this ascent? In much of the world, there is insufficient distribution capacity to connect solar producers to consumers, and expanding “the grid” has proven expensive and time-consuming. The intermittent nature of solar power also creates limitations although better battery technology and improved distribution would solve much of this problem. Finally, with growing supply and falling prices, there is a concern that falling returns will crimp investment in the industry. While these are genuine issues, they are not new and their combined impact to date has done little to slow solar’s rapid growth.

Escalating tariffs are one new wrinkle to keep an eye on. Much of the developed world already imposes tariffs on Chinese solar module imports but their level is likely to increase in the years ahead. So far, declining solar unit costs have helped offset much of the tariff-related price hikes but whether this can continue remains to be seen. My bet is that the current excess production capacity is likely to keep global prices low for years. This is a good thing given the rising global demand for clean power in the years ahead.