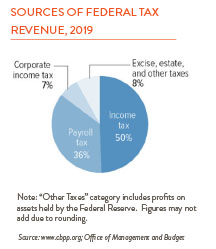

Eventually some version of Joe Biden’s big social spending bill will pass. While we don’t know the final price tag, we can be sure of one thing: higher taxes will be needed to pay for the wide range of health care, education, childcare, and climate initiatives embedded in the bill. To understand the proposed tax changes, it helps to step back and look at how our federal government levies taxes today. As the chart to the right shows, half of what the U.S. raises today comes from the personal income tax. Another 36% comes from payroll taxes – this includes the 12.4% that is used to fund Social Security and the 2.9% tax that funds Medicare. Of the remaining 14%, only half comes from corporate taxes. Given the funding challenges associated with Medicare and Social Security and the limited scope of corporate tax revenue, it is clear that the personal income tax will have to play a central role in any serious revenue raising effort.

Current proposals aim to raise approximately $2 trillion in new tax revenue. On the corporate side, there are two main initiatives: increasing the tax rate from 21% to 28% and expanding the tax on foreign earned income. Many of the tax breaks enacted in the 2017 tax reduction bill would also be eliminated. On the personal income tax side, the top “marginal” tax rate would rise from 37% to almost 40%. Those earning more than $5 million annually would face another 3% surcharge. Especially relevant for investors, the federal long-term capital gains rate for the wealthiest would rise from 23.8% to 31.8%. Changes to the federal estate tax are also possible.

There are a few things to note regarding these proposals. First, Joe Biden’s campaign promises included a pledge not to raise taxes on households with incomes below $400,000. That pledge together with broad voter concerns regarding income inequality are putting the very wealthiest Americans in the crosshairs. According to the non-partisan Joint Committee on Taxation, under the current proposals, households earning more than $1 million a year would see their taxes increase by 11% in 2023 while taxes would drop for those making less than $200,000.

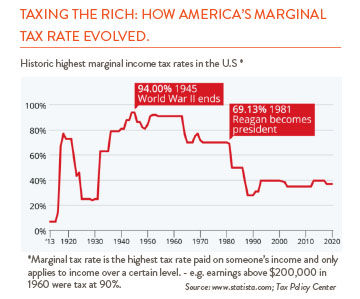

Second, while marginal income tax rates are likely to go up and no one likes higher taxes, tax rates would still be at historically low levels. As the chart above shows, between roughly 1931 and 1981, marginal tax rates exceeded 60%, sometimes by a substantial amount. Rates dropped to 50% under the Reagan administration and since 1987 have remained below 40%. The last tax increase occurred over 28 years ago. Since then, the substantial spending increases, under both Republican and Democratic administrations, have been largely funded by increased borrowing.

Finally, it is important to view U.S. tax policy in a global context. In a recent article, The Economist reported that in 2019, the U.S. had an overall tax-to-GDP ratio of 24.5% — a full nine percentage points below the average for our peer OECD developed countries. If enacted, the long-term capital gains rate would be at the high end when compared to our global peers while corporate rates would be about average.

It is too early for investors to start making portfolio adjustments given the uncertain state of the bill’s tax provisions. But there are a few things we do know today. Taxes are likely going higher in the years ahead. This means that any number of tax reduction strategies, things like capital loss harvesting and the use of tax deferred accounts, will become increasingly important ways to maximize after-tax returns – the key metric that investors of all tax brackets should keep an eye on.