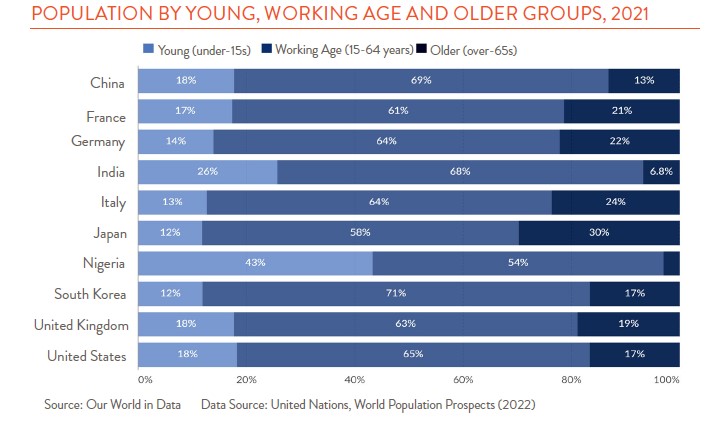

Those aren’t my words. I heard them from Shuntaro Takeuchi, a portfolio manager at Matthews Asia, and he wasn’t referring to the 1980 pop song by the Vapors, but to how aging around the globe is making the rest of the developed world look more like Japan. With 30% of its population over 65, Japan is the oldest country in the world. But Western Europe isn’t too far behind — and the U.S. is inching that way too.

“Japan’s present challenges are our collective future,” wrote Sarah Lubman for National Geographic last year (“Japan confronts a stark reality: a nation of old people”). Perhaps that’s why we can’t stop gawking. Japan is our living lab and test case for what happens when you get to this point. Japan’s population peaked in the 2008-2010 period and has been shrinking since. Labor shortages are evident everywhere.

The mainstream press prints plenty of stories to satisfy our curiosity – from the dire (more elderly are dying alone), to the techno-optimist (robots can do it all!), to the weirdly fascinating (“The gang’s gone grey: majority of yakuza in Japan now over age 50” – a headline from Asahi Shimbun). The reality is multifaceted, but Japan certainly hasn’t shied away from it. And in some ways, being ahead of the curve has forced innovation and put it in a position to export its learnings.

Japan has excelled at factory and service sector automation to alleviate labor shortages. But Japan is about more than robots. It also has built supportive policies and a variegated patchwork of initiatives from government, business, community, and individuals.

The government has been incentivizing citizens to work into their 70s – a new idea for many (the average life expectancy in Japan is 87 for women and 81 for men). And while Japan often is viewed as immigration-averse, it has started increasing targeted immigration with a fast track to permanent residency for those with certain skills. The government also provides generous long-term care, covering 70% to 100% of the costs from mandatory contributions from all workers over age 40. More recently, some municipalities have been experimenting with continuous support services for the elderly who live alone.

What is most impressive, though, are the many little creative things that individual communities and residents have done to keep the elderly mobile and independent for longer. In hollowed out towns where the shops have disappeared, there now are mobile supermarkets – grocery-laden trucks appearing once or twice a week so the elderly can shop close to home. Both small towns and housing complexes have organized senior transport services. They’ve also set up drop-in centers where elderly residents can get help with a wide range of tasks – like filling out forms or reviewing medication instructions. The city of Matsudo established a network of drop-in cafes for residents with cognitive decline who are disoriented or lost – and it’s trained over 20,000 volunteers as “dementia supporters” who know what to do when they encounter someone who needs help.

Business opportunities have arisen too, including “age-tech” startups and a wealth of new services like after-death deep apartment cleaning.

The ultimate lesson from all this may be the way Japan has confronted reality head-on rather than dodging the unpleasantness. True, Japan has no choice now, but all sectors of society seem to be energetically embracing problem-solving and continuous experimentation. Most of us would prefer not to think about what aging looks like. A quick Amazon search here for “aging” brings up lots of books on living gracefully and staying vital for longer – plus a few face creams and serums to help you look younger. But there’s little on how to manage when you can’t shop, navigate a public restroom, or get to the doctor on your own. That is where Japan is now – and it continues trying new things, big and small.