In our line of work we are privy to a lot of preconceptions surrounding estate taxes. Some of these ideas make sense, while many are outdated, overlook the added nuance of state taxes, or misunderstand the impact of gifting. Note: an estate lawyer is the ultimate source for good information!

Many people who began estate planning 10-20 years ago have anchored their understanding on a moving target—and it’s still moving. In 2001, for example, the federal estate filing threshold (exemption) was much lower at $675,000, and the top tax rate was 55%. A million dollar estate used to owe a good chunk of tax. Then in 2010, the estate tax was temporarily repealed—if you were going to die with a large estate, that was a great year to do it! By 2023, the estate tax has long been back in force, but the thresholds are much higher ($12.92 million) and top tax rates materially lower (40%). However, an important caveat is that the $12.92 million exemption is set to sunset in 2025 and will revert to around half that unless Congress approves new legislation. It’s no wonder the topic is confusing.

Here’s a brief example of what the current numbers mean. If someone dies in 2023 and their taxable estate exceeds $12.92 million, the estate owes tax on the value above that threshold. For an estate valued at $14.92 million, tax would be paid on $2 million.

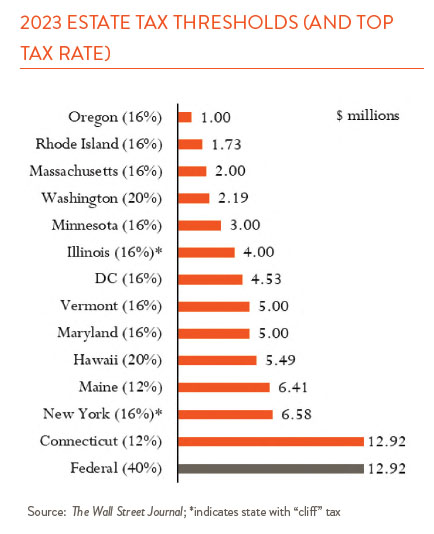

But that’s just for federal estate taxes. While most states do not have a separate tax, there are thirteen states (including DC) that do, and their thresholds and rates vary. The chart below shows these thresholds, ranging from a low of $1 million in Oregon to Connecticut’s matching the Federal level. For nearly all these states, tax (at varying rates) is applied only on the value above the threshold. However, Illinois and New York employ a so-called “cliff” tax, where the rate applies to the entire estate—including amounts below the threshold!—once the threshold is breached (or exceeds it by 5% in NY’s case). That’s a big deal.

Six other states make it even more complicated by levying an inheritance tax, with rates imposed in different ways depending on the relationship of the inheritor with the person who died. Only Maryland levies both.

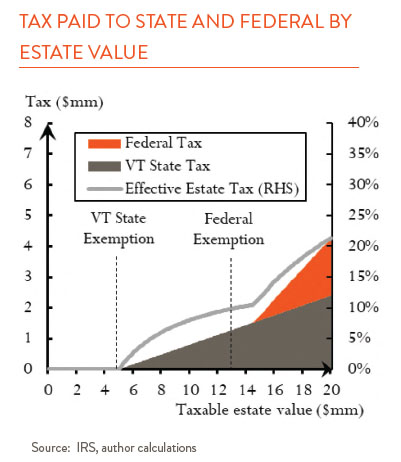

The other thing to note about state estate taxes is that they are deductible from federal estate taxes, reducing the value of the estate. Using Vermont as an example in the chart on the right, an estate pays no state or federal tax until it exceeds Vermont’s $5 million exemption. At that point it pays Vermont’s 16% rate on the amount above $5 million. As the value approaches the federal threshold, the estate is set to pay around $1.5 million in taxes to Vermont. But because of the state tax deduction, the estate has to be valued around $1.5 million higher than the usual federal threshold, or around $14.5 million, before it starts paying federal taxes on top of state taxes. I guess that’s good news?

Finally, on the gifting front, tax law allows you to give $17,000 (in 2023) per year to an unlimited number of individuals, tax-free. Many believe gifts above that tax exemption will be automatically taxed. Instead, “excess” gifts are added to (“unified” with) the estate. So in general, the gift is only taxed if the estate plus cumulative excess taxable gifts breach the state or federal estate tax thresholds. The flip side of this is that only gifts under the exemption reduce your taxable estate. Of course, donating to charities or paying others’ medical bills or education do reduce your estate and aren’t subject to gift tax.