The weekly pilgrimage down the driveway with garbage and recycling in tow is a common rhythm of domestic life. The conscientious among us take the additional time to rinse and sort. Many of us have two bins, and may have seen those “sorted” bins end up in the same truck! So what really happens next and where does the journey end for our trash?

You’ll be happy to learn that collection trucks are equipped with compartments for mixed solid waste and recycling, so our sorting isn’t in vain. But you will be less happy to learn what actually happens with our waste. That is the subject of the new book Waste Wars by Alexander Clapp. It is also the topic of this special “Garbage Issue” of the newsletter. We will be leaning heavily on Clapp’s work to explore what’s really going on and some of the dynamics involved as a plastic jar, for example, makes its way from the end of your driveway to be burnt in the Malaysian or Turkish countryside.

But first, a brief orientation. Most of the trash we don’t attempt to recycle stays relatively close to home and ends up in a landfill. That accounts for around half of our overall waste, which is nearly five pounds per person, per day (yikes). The number of active landfills has decreased in the U.S., with larger regional facilities replacing local ones. Here in Vermont, there is only one open landfill, in Coventry, which handles most of the state’s waste. Nationally, a smaller percentage of our trash is burned instead of buried, at times producing energy (and emissions) in the process

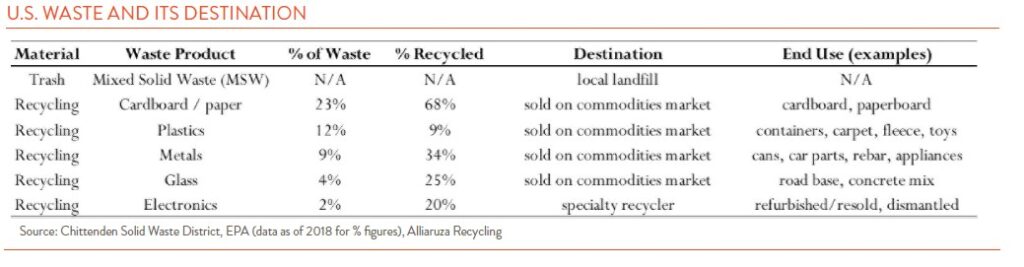

Recycling has a more complicated path. Much that could be recycled still ends up in the landfill. The rest is sold on the recycled commodities market to the highest bidder. But only about 60%-65% of the items we intend to recycle are actually given a second life. That number is shockingly low for some materials, like plastics, at 9% (see table below).

While our domestic recycling capabilities have improved in recent years, spurred by China’s 2018 ban on importing solid waste, still some 25%-30% of items intended for recycling are shipped abroad. A portion ends up in unregulated dumps, waterways, and “trash towns,”

where entire local economies depend on the processing, parsing, and selling of European and American garbage. The flow is typically from higher income countries with much larger consumption per capita to lower income countries with more lax environmental regulations. And don’t let the percentages fool you, it all adds up to millions of tons of waste exported from the U.S. alone.

The remainder of this issue will explore these topics. We will dive into plastics and then the special case of electronic waste (E-waste), which cannot be recycled with typical items or sent to landfills. We will conclude with some perspective on how we got here and what we might do to improve the situation. This issue does not make for light fare. We hope it makes us all think a little more about what we do with our garbage, and what we consume in the first place.