Investment advisors have a mixed track record when it comes to predicting things like interest rates, stock prices, and inflation. So it was with some sympathy that I turned to a recent New York Times article that featured eight Opinion columnists’ incorrect predictions over the years. If a luminary like Paul Krugman can get things wrong, after all, then maybe the rest of us can feel better for having a cloudy crystal ball.

In his piece, Krugman summarizes the intense debate between economists back in 2021 about the potential inflationary impact of the $1.9 trillion Covid stimulus package. For those who are scratching their head today wondering how we ended up with almost double-digit inflation, his piece is a good reminder that nothing as complex as the U.S. economy is easy to predict. David Brooks reviews how his thinking about Capitalism has shifted over the years. Farhad Manjoo and Zeynep Tufekci write about the early days of social media and how their enthusiasm for this new, disruptive force prevented them from seeing some of its darker sides.

These pundits got things wrong for several reasons. Expecting the future to look like the past was the most prevalent problem. This error, which Brooks describes as an “intellectual lag,” seemed most common when the signals alerting one to changing conditions were infrequent and/or imprecise. Several columnists admitted to the tendency to “believe what you want to be true.” Falling into “wishful thinking” prevented Tufekci, for example, from understanding the limitations of the internet as a force for social change. Finally, several of the writers admitted that they simply failed to understand the complexity of the issues at hand when making their predictions.

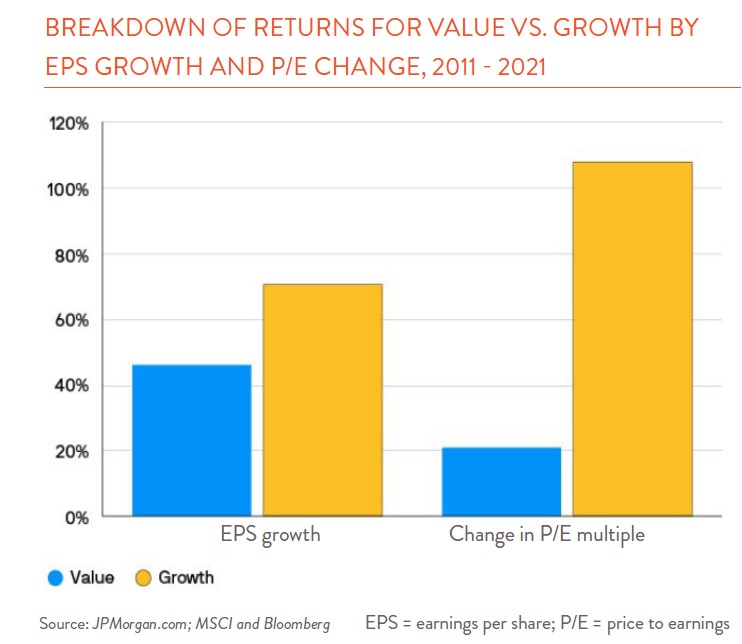

What have we gotten wrong? After 25+ years the list here is long. One that comes to mind, however, relates to how we select stocks. Our firm’s roots are based in the school of Value investing. This investment style places a heavy emphasis on the price you are willing to pay for a company’s future stream of earnings. Valuation metrics, which focus on the price of a firm’s shares relative to the book value of assets, proved a profitable way to identify investments for decades. But a few things shifted around mid-2007 to make this approach less effective. First, facing a weak economy, investors sought out firms that looked like they were growing fast and bid up their valuation multiples (see chart below). At the same time, rock bottom interest rates made them more willing to pay up even for firms whose profits were likely to appear, not today, but years in the future. While we were willing to pay high prices for the shares of some quality companies, paying nosebleed prices for firms with little to no earnings required too much of a shift in our thinking. Fortunately, our valuation discipline kept us out of any number of disasters (remember WeWork?), but it also left us underweighted to some of the market’s emerging tech stocks like Amazon. Value has soared back into favor this year thanks, in part, to rising interest rates, but this past period of underperformance was a painful one.

What have we learned? Today, we are much more flexible in our thinking. We continue to pay close attention to a company’s earnings but we are more willing to think broadly about how we value those earnings. We recognize that a firm’s value includes not just financial statement items like assets and earnings, but other factors that support its sustainable competitive advantages. Finally, we try to avoid some of the intellectual mistakes outlined above and recognize that some things are just too complex to forecast.