With the banking crisis and collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March, and now First Republic, we were anxious to take a look at the recently reported first quarter bank earnings. The following is a brief summary of what we learned.

Deposit flows were not straightforward.

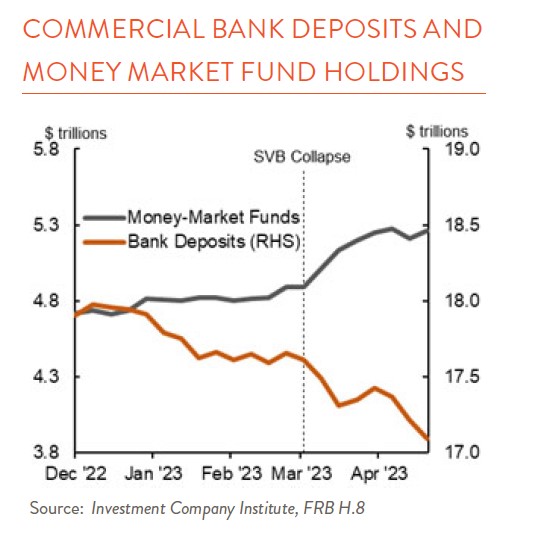

Deposit flight—a bank run—is ultimately what doomed SVB, and this was our first chance to get a bank-by-bank look at how others fared. It turns out, deposit flows were not that straightforward. Most banks experienced deposit outflows, but many pointed out that the declines had little to do with panicked behavior and were roughly in line with projections. Deposits had already been leaving banks as customers looked for higher-yielding alternatives. Money-market mutual funds have seen large inflows as they are able to increase their yield along with the Fed’s rate hikes (see chart, above).

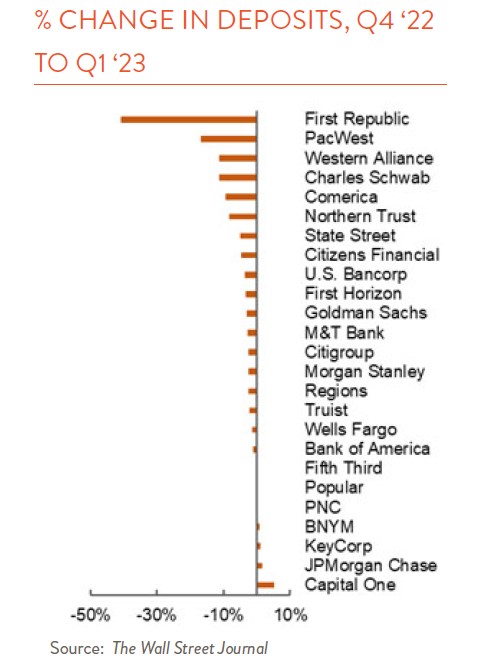

Of course, some banks experienced much larger outflows (see chart, below), and the stability of deposits seemed to be influenced by many factors including the type and location of its clientele, the diversity of its services, the size of the institution, its asset mix, and the share of deposits that were uninsured (above the $250k FDIC limit). As Bloomberg’s Matt Levine explains, deposits are technically short-term funding for a bank in that they need to be paid out to customers on demand, but in practice they are often treated as long-term funding because of the banking relationship and the hassle of switching accounts. What we are learning is the extent to which deposits are short-term and sensitive to information, or long-term and insensitive to information in the current environment. Thus far, it seems, it depends on the bank.

Bank profitability has declined.

Current conditions are not permanent, but for now, bank profitability is being squeezed. Banks are earning relatively little on the loans they issued and securities they bought at low fixed interest rates during the pandemic, while they are increasing what they pay to depositors as the Fed raises rates. Additionally, withdrawn deposits have had to be replaced by other, more expensive sources of funding, in some cases including the various—and expensive— liquidity facilities offered by the Fed and the Federal Home Loan Banks. In the extreme case of First Republic, Marc Rubinstein, who writes the Net Interest newsletter, found that they went from funding almost entirely from deposits that cost them 1.4%, to around half their funding coming from these official facilities that cost them around 5.0%. All the while, they earned just 3.7% on their loan and securities assets.

Commercial real estate remains a concern.

Q1 also showed an increase in “provisions for credit losses,” or money banks are setting aside in case a loan they’ve made defaults. The increases were primarily driven by commercial real estate (CRE) loans, given changing office-use dynamics and how expensive it is for borrowers to refinance at higher rates. CRE loans are more highly concentrated at the small, regional banks, and there is some concern about how CRE could pose an additional challenge to these already beleaguered banks.

Beyond those three themes, the main thing we learned was that it is hard to generalize about banks, especially in this environment. There is a lot of nuance related to size, business model, market, funding mix, and asset mix—all of which play a role in the bank’s ability to weather the storm and its profitability going forward.