At Hanson + Doremus, one of the primary qualities we screen for in prospective companies is the presence of an economic moat. While I am still relatively new here, I spent the last nine years as a senior equity analyst at Morningstar where moats are so highly thought of that the concept forms the foundation for the firm’s stock research philosophy. So why are moats important?

The concept is neither exclusive to Hanson + Doremus nor new. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor and chairman/CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, popularized the term and has used it in his widely read annual shareholder letter well over 20 times since 1986. Buffett describes a moat as the qualities that defend the valuable “castle” (i.e. the company) from external threats (i.e. competitors). A firm with an economic moat owns a durable competitive advantage that allows it to outperform its competitors over several years. In theory, a moat should help the firm earn excess cash flows and higher returns than its peers. This advantage is durable if the moat protects these returns persistently, for a decade or more. Higher returns in terms of cash flows over multiple years should increase the intrinsic value of the company.

At Morningstar, the obsession with moats meant the firm attempts to add some rigor to a process that remains as much art as science. We would look qualitatively for the presence of a moat from five potential sources:

- Intangible assets are brands, patents, proprietary technology, and regulations that allow firms to charge more for their products.

- Cost advantage is the ability to produce goods or services at a lower cost than competitors and thus offer lower prices or generate higher margins. This advantage is usually the result of size, closeness to customers, and/or lower cost of raw materials.

- Switching costs are the one-time costs customers incur when changing from one product/service to another. The costs, in terms of money, time, risk, and/or hassle, can sometimes be high enough to deter the switch.

- Efficient scale exists in markets small enough to be served by one or a few companies. New entrants are deterred from entering since returns won’t be large enough to survive (examples include regulated utilities, wireless telecom, and railroads).

- Network effects provide a moat when new and existing users gain value from a good or service as more users join the network. Economic profits to the firm must also increase with users, as with Facebook, eBay, or Windows.

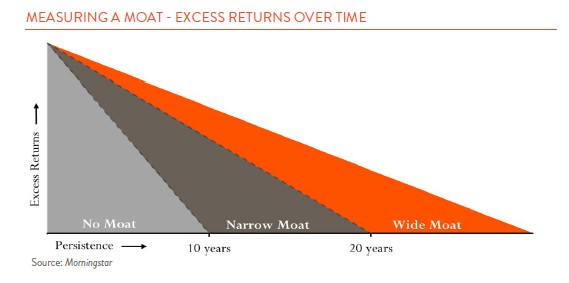

Analysts also use a quantitative screen to understand how durable a moat is. For a “narrow” moat, the analyst’s cash flow model must deem the firm’s excess profits are more likely than not to persist for more than ten years. For a “wide” moat, this advantage must persist for more than 20 years. Companies whose excess profits disappear less than ten years into the future receive no moat rating (see chart at bottom).

For a brief example, we can turn to Costco. Costco’s wide moat comes from cost advantage and intangible assets. The cost advantage is evident to anyone who has shopped at the firm’s no-frills warehouse stores. Costco offers a low number of products (4,000 SKUs) relative to either Target (80,000 SKUs) or Walmart (140,000 SKUs), simplifying both procurement and supply chain logistics. Additionally, the modest annual membership fees generate enough income to allow the firm to offer very low prices. The intangible assets for Costco are its deep supplier relations and vast consumer data set, which help with selecting the right products for both national and local distribution. As a result, Costco has been able to generate excess returns consistently for decades.

While moats are very important, we don’t simply invest in every firm with a wide moat—and there are good investments that have no moat at all. We examine a mosaic of information that also includes company fundamentals, opportunity costs, portfolio construction considerations, and other factors. And of course, as value investors, we care deeply about the price we pay for what we’re getting.