The Federal Reserve is in the news a lot. With inflation running hot, everyone is trying to figure out how high the Fed will raise interest rates. At Hanson + Doremus, we are not trying to guess where rates end up, but we do think it is important to understand the Fed and its thinking around inflation.

The Fed’s goals are maximum employment and stable prices, the latter defined as two percent inflation. The Fed’s main tool to achieve these objectives is the control of short-term interest rates, especially the “federal funds” rate at which financial institutions borrow from one another. By raising interest rates, the Fed makes borrowing more expensive. The thinking goes that this results in fewer projects and slower hiring, reducing wage growth and the demand for goods and services, and thereby reducing the rate of inflation.

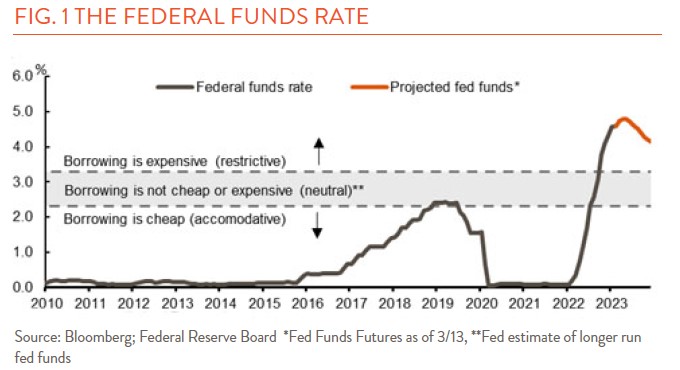

The Fed has now raised interest rates from zero to 4.5 percent with further increases expected (Figure 1). That is well into the territory they believe is restrictive for economic activity and where they expect some impact on inflation. And yet, the latest inflation reading was 5.4 percent, well above the Fed’s two percent target. So how does the Fed figure out how deep into restrictive territory to go and how long to stay there? That depends on the impact the Fed thinks it is having on inflation, and therein lies the problem—it’s a little like feeling your way in the dark.

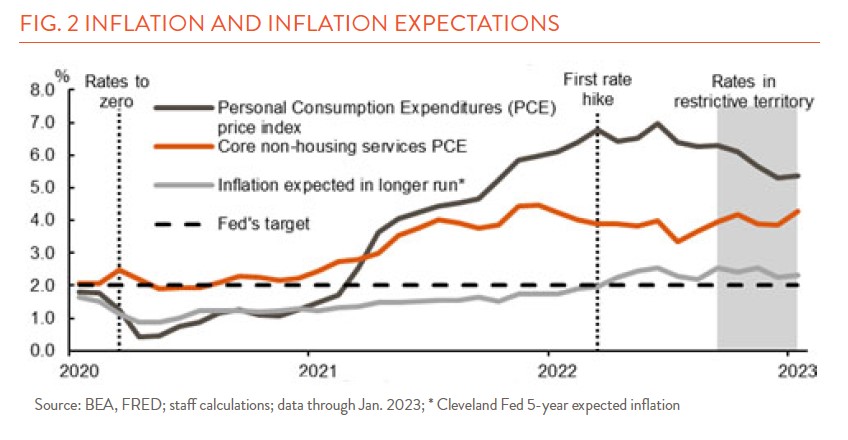

First, the Fed recognizes “long and variable” lags between changes in interest rates and their impact, so the Fed does not get feedback until some unknown future date. Second, the feedback itself is not clear. Inflation data are noisy, and the Fed is currently relying on less than half the prices in the economy, so-called “core non-housing services,” for signs of the impact of rate hikes. Finally, the Fed believes psychology plays a role, and psychology can be fickle. The risk is that if people come to expect higher inflation in the future, they will buy more today, pushing prices up even faster. To prevent expectations from taking off, the Fed is inclined to talk and act aggressively.

Looking at Figure 2, it is hard to know yet whether the Fed is succeeding in reducing inflation. Since they began hiking rates last spring, big picture inflation (dark grey) has come down, but their watchpoint inflation number (orange) remains elevated. Longer run inflation expectations (light grey), however, are still around the Fed’s two percent goal.

Another dilemma is that by trying to push down inflation, the Fed might cause a recession. The labor market and economy have thus far proven resilient to higher rates, but the Fed needs them to slow down because their strength contributes to inflation. However, continuing to raise rates to get back to two percent inflation could involve slowing growth to the point of recession, or exposing business practices born of the low-rate environment that suffer with higher rates. Right now, presented with the risks of runaway inflation versus slower growth, the Fed has indicated it will side with more rate increases to tamp down price increases. This does not paint an encouraging picture for the chances of a “soft landing.”

The Fed meets next week and will update their projections for the federal funds rate and inflation over the next several years. What actually ends up happening probably won’t follow that script, but these estimates will shed some light on the impact the Fed thinks it is having on inflation and how long they expect to keep rates in restrictive territory.