With tariff chaos and geopolitics dominating headlines, you would be forgiven for missing the news around Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In fact, you’d be forgiven for recognizing the names but not knowing what (who?) they are and what they actually do. We’ll get to that, but the story is that the Trump Administration is pushing to release them from government conservatorship, which could be a big deal for housing finance.

The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie) guarantee mortgage credit risk, i.e. the chance that you and I don’t pay our monthly principal and interest. That guarantee makes it much more attractive for investors to buy single-family mortgages, which makes mortgage credit cheaper and more available, thus supporting the housing market and home ownership.

While Fannie and Freddie are technically private corporations, they were established by Congress and are “Government Sponsored Enterprises” (GSEs). GSE status has meant the mortgage credit guarantee also comes with implicit backing by the U.S. government. That implicit backstop became overt during the financial crisis when the U.S. Treasury bailed them out by buying equity in each company and taking them into conservatorship. Now, Trump, building on his first term effort to reduce government involvement in housing finance, is keen to release them. How that happens matters, and the fear is that without the government involved, it could push mortgage rates higher.

Some context is warranted. When we get a mortgage from the local bank or a non-bank, such as Rocket Mortgage, most of the time that institution acts as the “originator” of the mortgage and continues to “service” the loan. Behind the scenes, however, these institutions typically sell mortgages on to Fannie or Freddie, who then group hundreds or thousands of those loans into pools that they wrap up in their guarantee (for a fee). They then sell those pools onto investors. This process is called “securitization”, and the result is a “mortgage-backed security”, or MBS.

So at the end of the day, it is the MBS investor who finances your home. The price at which they are willing to do that depends on many things, including the credit risk bedded in the pool of mortgages. Right now, investors view residential mortgage credit risk as Fannie and Freddie’s credit risk, which is implicitly the U.S. government’s credit risk, i.e. a very low risk of default. If Fannie and Freddie are released from conservatorship that could change. Investors may ask themselves, is this risk more like the U.S. Treasury, or more like just another corporation? For context, corporate bonds usually have higher yields to compensate investors for the additional risk.

However, Trump sounds committed to minimizing the impact on mortgage rates and in May he posted, “I want to be clear, the U.S. Government will keep its implicit GUARANTEES”. That’s pretty explicit.

The other component is the fee the GSEs charge to guarantee the credit risk, called the “G-fee”. Right now, that fee accounts for around 0.50% of the interest rate on a mortgage. But if released from conservatorship, the GSEs may decide to increase the fee to earn higher profits or for other reasons, like if their regulator requires them to buy catastrophe insurance, for example.

That said, all of this may be many years down the road. The GSEs have been in conservatorship for nearly two decades and plenty of people are just fine with that. If they are released, there are many thorny issues to confront, and for all its jawboning, the Administration has been light on details. For example, how will the Treasury’s current funding be replaced? As financial institutions, the GSEs need to maintain certain leverage ratios—how much equity should they hold relative debt? Is the equity raised through public offering? Will the government retain some amount of ownership?

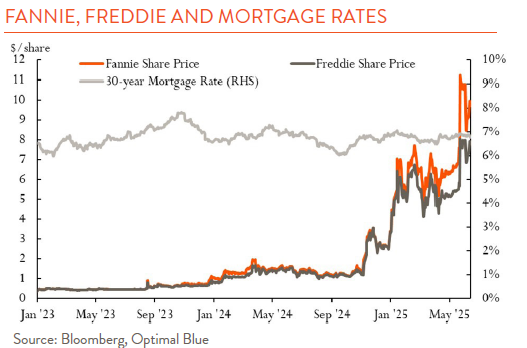

Headlines have centered around certain hedge funds that bought shares in Fannie and Freddie a decade ago and have a vested stake in how this plays out to maximize their return. And investor enthusiasm, at least as measured by the price of the common shares of equity still available to the public, has risen sharply since Trump was elected (see chart above). But for most of us, what really matters is the impact on mortgage rates. Thus far, there has been no discernible impact, and it is important to remember that Fannie and Freddie existed on their own for years, but we should not lose sight of how this unfolds.

The housing finance market has spent many years optimizing around Fannie and Freddie being in conservatorship. Tweaks to that, even benign-seeming ones, could gum up the works, cause investors to re-evaluate the suite of risks in single-family MBS, or allow the GSEs to pursue profit over more accessible housing credit. Any of these scenarios could result in higher mortgage rates—not something any of us looking to finance a home would be especially happy about.