The world’s current struggles with waste are not new. Many of us first became aware of the problem in the 1980s as recycling programs across the country gained steam. Since then, a steady stream of regulations at both the domestic and international levels have done little to stem the tidal wave of waste. Is there any hope for large scale solutions or are we destined to live in a world of ever-growing trash?

Further efforts to reduce waste must be based on a deep understanding of the problem and how we got here. In the wake of WWII, rising income levels, falling manufacturing costs and the development of plastics all contributed to growing waste volumes. The statistics in this issue, based largely on data from Alexander Clapp’s recent book Waste Wars, highlight the explosion of waste fueled in large part by the growth of plastic, single-use products.

In addition, growing environmental regulations have had some perverse negative consequences. With tougher regulations came higher costs and the move to ship ever-growing quantities of waste from the developed world to countries with the lowest costs and least environmental controls. Recycling mandates too have helped relieve our guilt by convincing us of the limited environmental impact of our consumption patterns. Throwing your plastic Starbucks cup in the blue recycling bin, for example, may make you feel better about buying the next one. But as we’ve outlined in this issue, this move is hardly “costless” from an environmental standpoint.

Unfortunately, there is no “magic bullet” waiting to solve the globe’s growing waste dilemma. The waste market – for plastic, steel, paper, and E-waste – is not one market, but many. Because each has its own distinct supply/demand characteristics, technical recycling challenges, and varying global regulations, no one solution is likely to work for all. Ultimately, future waste mitigation efforts will need to take several forms. Since the problem is largely related to consumption, it is tempting to think that, with the right information, consumers will alter their own behavior. History shows, however, that relying on individual action alone is unlikely to solve the problem.

Further regulatory reforms offer more promise but are complicated by the fact that there is no one, global regulatory enforcement authority. Still, further coordinated efforts should not be discounted. The United Nation’s Environmental Assembly is currently negotiating a new Global Plastics Treaty. When signed, this Agreement, which includes over two hundred countries, aims to address the full lifecycle of plastics from production and design, to waste management.

More generally, policies aimed at shifting the responsibility to manufacturers, so called “Extended Producer Responsibility,” could help incorporate the cost of recycling and disposal into the price of consumer goods. They could also provide companies with an incentive to innovate on sustainable product design and packaging. On the consumer side, “Pay As You Throw” policies that charge by the pound for waste (with recycling sometimes free, as an added incentive) can help keep our consumption of disposable products top of mind. Finally, a range of emerging technologies will help. Examples under development today include the use of robotics and AI to make waste sorting efforts more efficient and on the material science side, more biodegradable packaging solutions.

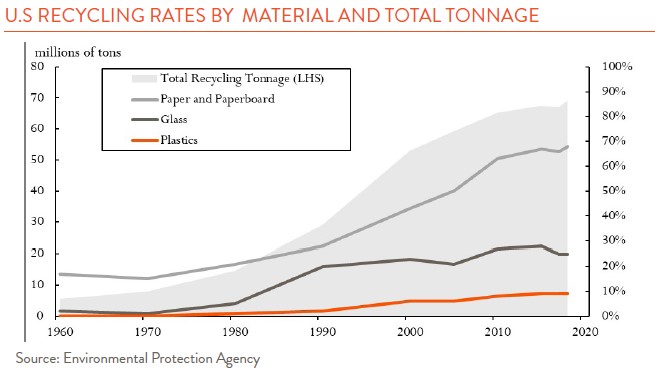

What can each of us do to help solve this global problem? First, reducing consumption of single-use products will have the biggest impact. In addition, we can avoid electronic products with short life spans (i.e., planned obsolescence) while favoring companies making real progress toward sustainable packaging goals. Second, get educated. Keep in mind that while recycling volumes in the markets for steel and paper have grown meaningfully, these efforts are rarely “clean.” And recycling rates for many materials like plastic remain low (see chart left). As the chart on page 1 of this issue illustrates, local solid waste districts and state/federal environmental agencies can be helpful sources when trying to determine where our waste goes. The title of Alexander Clapp’s book, Waste Wars, is apt. This work will indeed be a war, and a long one at that.