Worker shortages are a problem. Everywhere. You know it if you’ve been looking to hire – or trying to see a doctor, renovate a kitchen, or pick up your burger and fries. Everything is harder and takes longer when the help is not there. Whether it’s railroad workers or accountants, there just are not enough of them.

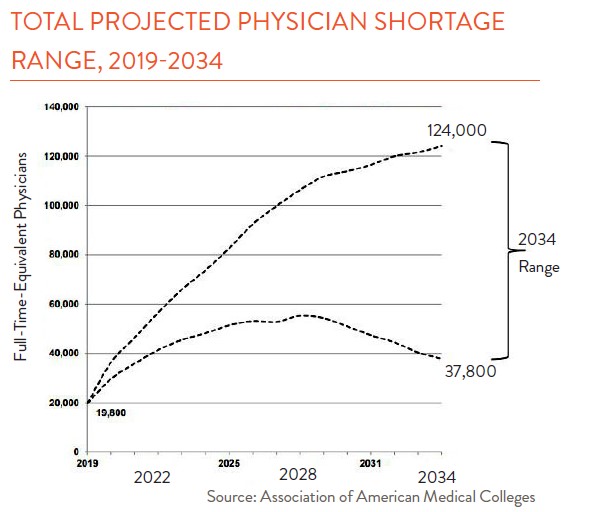

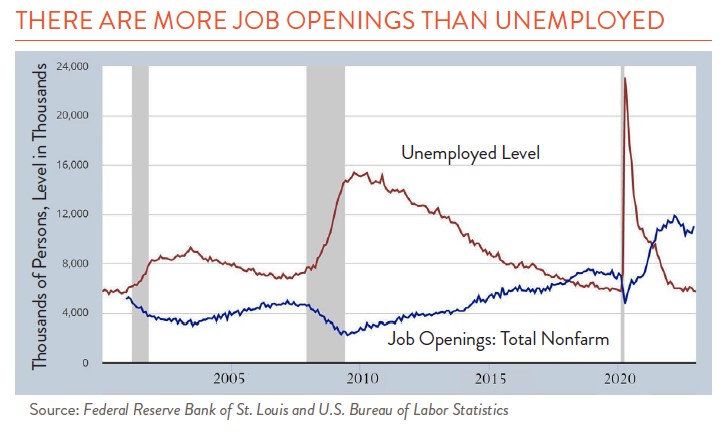

January data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) showed over 11 million job openings but only 5.7 million unemployed — and the shortages are widespread. We know there aren’t enough nurses, teachers, retail workers, or childcare providers. But what about plumbers? The National Association of Home Builders says we need 55% more. And doctors? The Association of American Medical Colleges sees a deficit of anywhere between 37,000 and 124,000 U.S. doctors in the next decade, a looming public health crisis.

The early pandemic narrative was that workers were quitting in droves because they were burnt out, fed up, and flush with savings. But Covid is receding now, and there seems to be something deeper and longer-lasting at work. Last January, IBM CEO Arvind Krishna said, “. . . I don’t believe that the skill shortage is because of Covid. I do believe Covid may have exacerbated or created a pull-in of those demographics, but those, I think, are going to last us for a decade.” And he may be right. Certainly, demographics are working against us. And certainly, we have some long-run skills deficits that Covid highlighted or accelerated through economic dislocation.

Burnout, demographics, and skills deficits sometimes combine in spectacular ways. Going back to doctors, the Association of American Medical Colleges says almost 30,000 new doctors completed their education and entered the workforce the last year, but 117,000 doctors retired – and some below traditional retirement age were exhausted from the pandemic. About 45% of U.S. doctors are over the age of 55, making for poor demographics. And becoming a doctor takes a long time and is hard, which has many asking if it is too hard and too discouraging.

Those also are questions for the field of accounting and auditing, which isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but as Adrian Wooldridge of Bloomberg wrote, “Capitalism can’t function without a healthy system of accounting.” The number of accountants and auditors fell by 17% between 2019 and 2021, and half the people who take the CPA test each year fail. Plus, with more regulation and things to account for, the job is only getting harder.

We shouldn’t lose hope about working our way out of this, but even optimists must speculate that solving labor issues will take a long time. In the shorter term, weak economic conditions could force more people back into the work force, including early retirees. But demographic challenges and skills deficits are long-term issues. All professions are going to have to compete harder for a dwindling pool of people. At the same time, as automation and AI pick up more of the slack, as they surely will, skills requirements will change even more dynamically.

The January BLS data revealed that the two occupational categories with the lowest unemployment rates (at a slim 1.5%) were health practitioners and “computer and mathematical occupations.” Yes, despite all those layoffs, techies still are needed. When Peter Coy of The New York Times looked into the tech skills most in demand, he read that the number one was MapReduce, “which,” he wrote, “I admit I had never heard of.” Then he wryly added, “A good way to make yourself feel clueless is to read all the other must-have skills that, unless you’re in tech, you probably know nothing about. Here are Nos. 2 through 12: Go/Golang, Elasticsearch, Chef, Apache Kafka, service-oriented architecture, Teradata, Redis, PAAS, Kubernetes, Containers and Amazon Route 53.”