In fact, with all due respect to Mick Jagger and the Stones, you can’t get what you need now either. Global supply chains still are roiling profits and plans. In General Electric’s last earnings call, the words “supply chain” came up 24 times. For General Motors, they appeared 14 times. And for Tesla, there were 13 mentions, as in Elon Musk saying, “it’s been kind of supply chain hell for several years.”

The thing about supply chains is that no one really cares about them when things are going well, which they can for long periods. It’s only when things get mucked up – by natural disaster, geopolitics, pandemic, or other shocks — that everyone starts focusing on them. The Wall Street Journal recently reviewed a new book on procurement called Profit from the Source that said a job offer in procurement was once the career kiss of death, “the fast track to nowhere.” Not anymore.

Supply chains are the networks of people and organizations needed to create and sell products, from raw materials to final delivery. They include both production and distribution, and both are amazingly complex, which is why they are so vulnerable to shocks.

On the production side, the days of a single factory taking in raw materials and churning out a finished product are over. Instead, we have strings of specialized component makers and networks of sub-assemblies on top of sub-assemblies. The many components in your smartphone, down to the microchips, come from far-flung places – and so do the silicon needed to make the microchips and the quartz needed to grow the silicon.

Supply chain expert Willy Shih at Harvard Business School recently wrote in The Wall Street Journal that big companies can have so many tiers of suppliers, it’s hard to keep track of them. McKinsey, he says, estimates that a typical auto maker has 250 tier-one suppliers and 18,000 suppliers across all tiers. You may know what’s going on with your direct suppliers at tier one, but not at tier two or three – and it can be too late when you find out they have a problem.

Reduced competition within industries also plays a part in our supply chain vulnerabilities, says economist Diane Coyle at Cambridge. Specialization and higher industry concentration, often with a “superstar” firm at the top, mean there are fewer suppliers at each link of the chain. That’s a pressure that’s been building for four decades.

On the distribution side, things are no less complex. That gets fully demonstrated in Arriving Today, a new book by Christopher Mims, the technology writer at The Wall Street Journal. Mims spins a colorful tale of a simple USB wall charger going from assembly in Vietnam to a container ship bound for the Port of Los Angeles, and then to an Amazon distribution center and on and on before the last mile on the UPS truck (and there are plenty of robots and AI algorithms along the way).

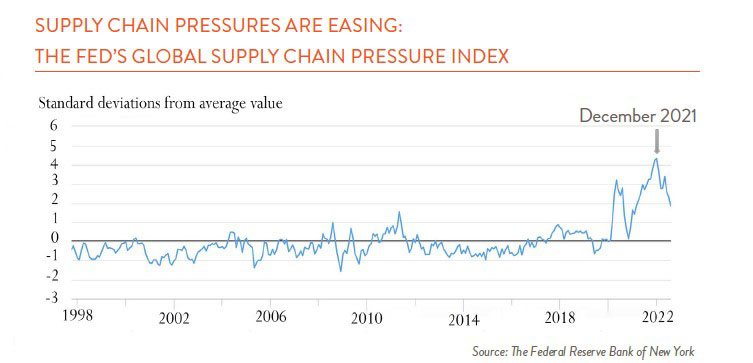

All this complexity means that recovery will take a while. The good news is that the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) shows pressures easing since a peak in December 2021. The GSCPI combines multiple measures like freight costs, delivery times, and backlogs into a single number, and improving conditions suggest that companies are showing ingenuity as they address challenges.

Still, we are not out of the woods by any means. That’s why we’re all talking about building supply buffers through redundant sourcing, reshoring, and “friend-shoring.” But none of these are immediate fixes, and all are costly.

The thing is, we’ve experienced supply chain disruptions before – from oil in the 1970s to the 2011 Thailand floods that wrecked our hard disk drive supply. We’ve had toilet paper shortages not just in 2020, but also in 1973. Each time, we vow to build buffers into our supply chains, but then it’s all too easy to forget. Competitive pressures eventually force companies to reprioritize profits, and the pendulum swings from resiliency back to just-in-time efficiency.

Perhaps this time, we’ll find a longer-term solution for balancing resiliency with cost. One interesting idea here, from Boston Consulting Group, is for companies to pool their risk with industry peers, much like insurance companies do, by building stockpiles of critical components only for use in a crisis for a shared fee.